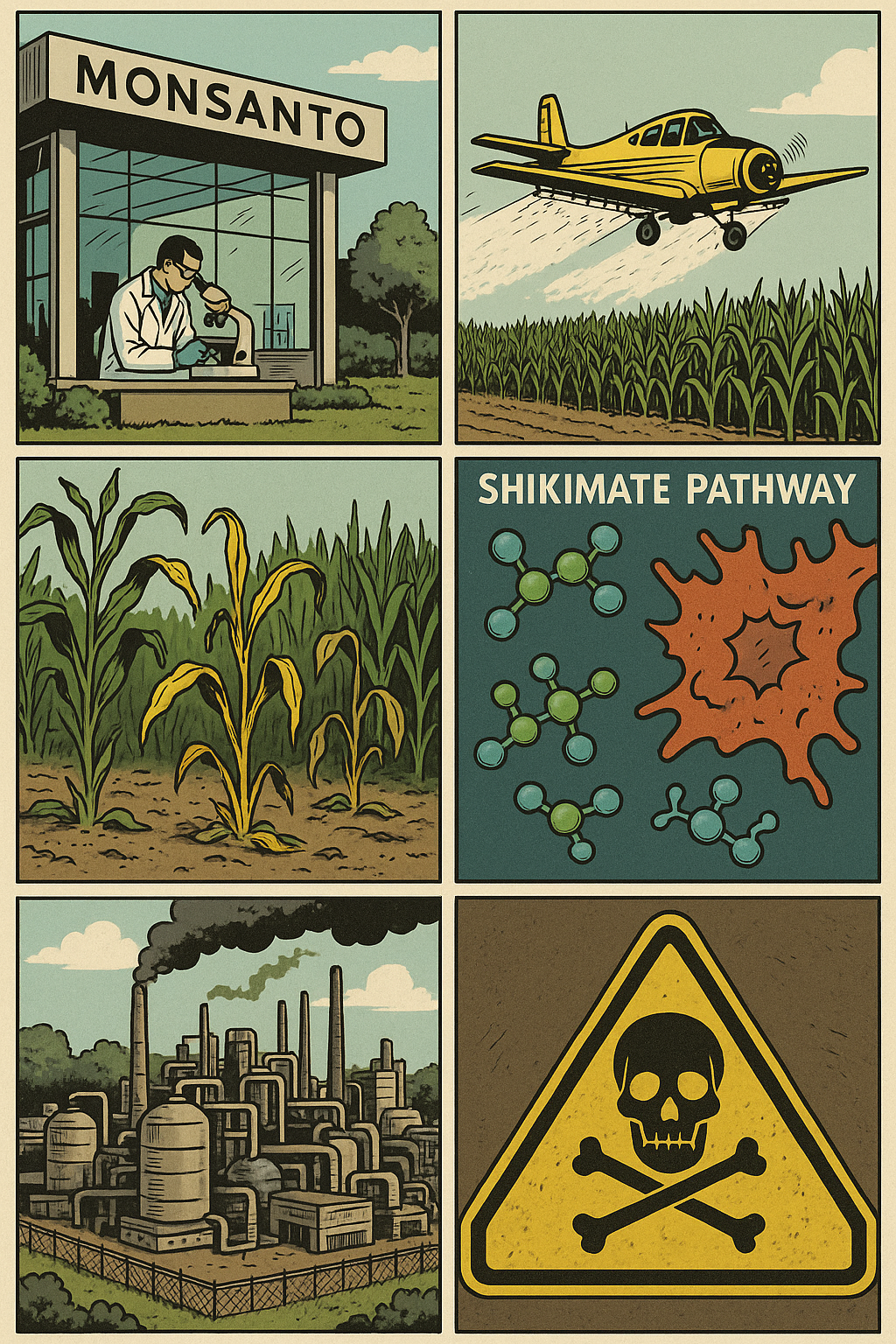

Toxic Glyphosate in Monsanto Round-Up

Glyphosate—the active ingredient in Monsanto’s Roundup—has been at the center of a global controversy encompassing health risks, environmental damage, regulatory failures, and corporate misconduct. While regulatory agencies like the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) have deemed glyphosate safe when used as directed, a growing body of scientific research, legal judgments, and internal corporate documents suggest a more troubling reality.

Scientific Evidence of Harm

Carcinogenicity and Cancer Biomarkers

- IARC Classification: In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), part of the World Health Organization, classified glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans” (Group 2A), citing strong evidence of genotoxicity and oxidative stress. (iarc.who.int)

- Human Biomarker Study: A 2023 study by U.S. government scientists found that individuals with higher glyphosate levels in their urine exhibited signs of oxidative stress, a condition linked to DNA damage and cancer development. (theguardian.com)

- Meta-Analysis Findings: A 2019 meta-analysis from the University of Washington reported a 41% increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma among individuals with high glyphosate exposure. (eatingwell.com)

Environmental and Ecological Impact

- Bee Gut Microbiota Disruption: Research published in 2018 demonstrated that glyphosate exposure disrupts the gut microbiota of honey bees, particularly affecting beneficial bacteria like Snodgrassella alvi, thereby increasing bees’ susceptibility to infections and contributing to colony collapse disorder. (en.wikipedia.org)

- Soil and Microbiome Effects: Studies have shown that glyphosate can alter soil microbial communities, potentially impacting soil health and fertility.

Legal Judgments and Corporate Accountability

Landmark Lawsuits

- Dewayne Johnson Case (2018): A California jury awarded \$289 million (later reduced to \$21 million) to Dewayne Johnson, a groundskeeper who developed non-Hodgkin lymphoma after extensive Roundup use. The court found that Monsanto failed to warn about the product’s cancer risks. (en.wikipedia.org)

- Recent Verdicts: In March 2025, a Georgia jury awarded \$2.1 billion to a plaintiff who alleged that Roundup caused his cancer, marking one of the largest verdicts against Bayer to date. (washingtonpost.com)

Settlements and Ongoing Litigation

- Mass Settlements: Bayer, which acquired Monsanto in 2018, has paid over \$10 billion to settle more than 100,000 Roundup-related cancer claims. (drugwatch.com)

- Pending Cases: As of mid-2025, approximately 67,000 cases remain unresolved, with Bayer considering a potential bankruptcy filing for Monsanto to manage the litigation burden. (wsj.com)

Corporate Misconduct and Regulatory Capture

Manipulation of Scientific Research

- Ghostwriting and Suppression: Internal documents, known as the “Monsanto Papers,” revealed that Monsanto employees ghostwrote scientific articles and suppressed unfavorable research to defend glyphosate’s safety profile. (wisnerbaum.com)

- Influence on Regulatory Agencies: Evidence suggests that Monsanto exerted undue influence on regulatory bodies, including the EPA, to downplay glyphosate’s risks. Reports indicate that the EPA relied heavily on Monsanto’s own studies, some of which were later found to be fraudulent. (wpln.org)

Legal and Political Maneuvering

- Preemption Defense: Bayer has argued that federal pesticide regulations preempt state-level failure-to-warn claims, seeking to limit liability through legal technicalities. (apnews.com)

- Lobbying for Legal Immunity: The company has lobbied for state legislation to provide legal immunity for pesticide manufacturers, with mixed success across various states. (apnews.com)

Global Regulatory Discrepancies

- Divergent Assessments: While the IARC has classified glyphosate as probably carcinogenic, agencies like the EPA and EFSA have concluded that glyphosate is unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans when used as directed. These discrepancies stem from differences in evaluation methodologies and the weight given to certain studies. (eatingwell.com)

- International Bans and Restrictions: Several countries and regions have imposed bans or restrictions on glyphosate use. For instance, France banned Roundup Pro 360 in 2019, citing safety concerns. (en.wikipedia.org)

Conclusion

The body of evidence challenging glyphosate’s safety is substantial and multifaceted, encompassing scientific studies, legal judgments, and revelations of corporate misconduct. While regulatory agencies have offered assurances of safety under specific usage conditions, the convergence of independent research findings and legal outcomes suggests that glyphosate poses significant risks to human health and the environment. The ongoing litigation and regulatory debates underscore the need for a precautionary approach and greater transparency in evaluating and managing the risks associated with widely used herbicides like glyphosate.

Glyphosate

- Type: Non-selective systemic herbicide

- Effect: Kills virtually all plants (grass, weeds, crops, etc.) by disrupting the shikimate pathway, a critical plant enzyme system for amino acid synthesis.

- Common Brand: Roundup (originally by Monsanto)

How It Works:

- Absorbed through leaves and green tissues.

- Translocated throughout the plant, including down to the roots.

- Blocks the EPSP synthase enzyme → halts protein synthesis → plant death.

Characteristics:

- Non-selective: Kills all vegetation it contacts unless it’s genetically modified to resist it (e.g., Roundup Ready crops).

- Visible result: Leaves wilt and turn brown within 3–10 days.

- Residual: Often claimed to break down quickly in soil, but this is contested in environmental and independent studies.

Other Chemicals With Similar Effects:

| Chemical | Notes |

|---|---|

| Diquat | Fast-acting contact herbicide (burns foliage only) |

| Glufosinate | Similar to glyphosate but less widely used |

| Paraquat | Extremely toxic, banned in many countries, fast-acting |

| Imazapyr | Soil-active, long-lasting, kills all vegetation including trees |

| Triclopyr | Used for woody plants, not as broad-spectrum as glyphosate |

If you want complete brown-out of all plant life, glyphosate or imazapyr are the two most likely to be used.

A comprehensive timeline of glyphosate’s history, legal battles, and scientific findings, with a focus on alternative and critical perspectives.

Glyphosate Controversy Timeline

1970–1990s: Introduction and Early Marketing

- 1970: Monsanto chemist John E. Franz discovers glyphosate’s herbicidal properties.(en.wikipedia.org)

- 1974: Monsanto introduces Roundup, promoting it as “biodegradable” and “environmentally friendly.”(en.wikipedia.org)

- 1996: New York Attorney General sues Monsanto for false advertising claims about Roundup’s safety. Monsanto settles without admitting wrongdoing. (en.wikipedia.org)

2015–2017: Rising Health Concerns and Legal Actions

- March 2015: The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans” (Group 2A). (iarc.who.int)

- 2015: First Roundup product liability lawsuits are filed against Monsanto. (bolingfirm.com)

- 2017: California lists glyphosate under Proposition 65 as a chemical known to cause cancer. (bayer.com)

2018–2020: Landmark Lawsuits and Settlements

- August 2018: In Johnson v. Monsanto Co., a jury awards \$289 million to Dewayne Johnson, a groundskeeper who developed non-Hodgkin lymphoma after using Roundup. The award is later reduced to \$21 million. (en.wikipedia.org)

- 2019: A jury orders Bayer (which acquired Monsanto in 2018) to pay \$2 billion to a couple who developed cancer after using Roundup. The award is later reduced to \$86.7 million. (en.wikipedia.org)

- June 2020: Bayer agrees to pay up to \$10.9 billion to settle approximately 100,000 Roundup lawsuits. (bayer.com)

2021–2025: Ongoing Legal and Scientific Developments

- 2023: A study by U.S. government scientists finds that individuals with higher glyphosate levels in their urine exhibit signs of oxidative stress, a condition linked to DNA damage and cancer development.

- May 2025: Approximately 67,000 Roundup cases remain unresolved, with Bayer facing mounting financial pressure as future trials stack up. (lawsuit-information-center.com)

Key Scientific Studies and Findings

Carcinogenicity and Health Risks

- 2015 IARC Monograph: Classifies glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans” based on limited evidence in humans and sufficient evidence in animals. (eatingwell.com)

- 2019 Meta-Analysis: University of Washington researchers report a 41% increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma among individuals with high glyphosate exposure.

- 2023 NIH Study: Finds that higher glyphosate levels in urine are associated with oxidative stress biomarkers, which are linked to cancer development. (theguardian.com)

Environmental Impact

- Bee Gut Microbiota Disruption: Research shows that glyphosate exposure disrupts the gut microbiota of honey bees, increasing their susceptibility to infections and contributing to colony collapse disorder.

- Soil and Microbiome Effects: Studies indicate that glyphosate can alter soil microbial communities, potentially impacting soil health and fertility.

Legal Judgments and Corporate Accountability

Notable Lawsuits

- Dewayne Johnson Case (2018): First major verdict against Monsanto, with a jury awarding $289 million (later reduced) to a groundskeeper who developed cancer after using Roundup.

- Pilliod et al. v. Monsanto Co. (2019): A California jury awards over $2 billion to a couple who both developed non-Hodgkin lymphoma after using Roundup; the award is later reduced to $86.7 million. (en.wikipedia.org)

Settlements and Ongoing Litigation

- 2020 Settlement: Bayer agrees to pay up to $10.9 billion to settle approximately 100,000 Roundup lawsuits. (bayer.com)

- 2025 Status: Approximately 67,000 cases remain unresolved, with Bayer facing mounting financial pressure as future trials stack up. (lawsuit-information-center.com)

Corporate Misconduct and Regulatory Capture

- Ghostwriting and Suppression: Internal documents, known as the “Monsanto Papers,” reveal that Monsanto employees ghostwrote scientific articles and suppressed unfavorable research to defend glyphosate’s safety profile.

- Influence on Regulatory Agencies: Evidence suggests that Monsanto exerted undue influence on regulatory bodies, including the EPA, to downplay glyphosate’s risks. Reports indicate that the EPA relied heavily on Monsanto’s own studies, some of which were later found to be fraudulent.

Global Regulatory Discrepancies

- Divergent Assessments: While the IARC has classified glyphosate as probably carcinogenic, agencies like the EPA and EFSA have concluded that glyphosate is unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans when used as directed. These discrepancies stem from differences in evaluation methodologies and the weight given to certain studies.

- International Bans and Restrictions: Several countries and regions have imposed bans or restrictions on glyphosate use. For instance, France banned Roundup Pro 360 in 2019, citing safety concerns.

Great, I’ll prepare a deep dive into glyphosate with a globally informed, neutral-to-critical tone. It will cover toxicology, cancer and endocrine links, environmental impact, regulatory and legal history, potential suppression of science, and alternative interpretations. I’ll include citations and links to primary sources and studies.

I’ll let you know when the full report is ready.

Glyphosate: A Comprehensive Investigation

Glyphosate is a broad-spectrum herbicide that has become the world’s most widely used weedkiller since its introduction by Monsanto in the 1970s. It is valued for its effectiveness on plants, but its pervasive use has also made it a focal point of health and environmental debates. This report provides a deep dive into glyphosate’s toxicology, links to cancer and endocrine disruption, environmental impacts, regulatory and legal history, allegations of corporate misconduct, and alternative or conspiratorial claims – all with a neutral, investigative lens.

Toxicological Profile

Glyphosate’s herbicidal mechanism of action is to inhibit the enzyme EPSP synthase in the shikimate pathway, which exists in plants and many microbes but not in humans or animals. The absence of this pathway in mammals is a key reason why glyphosate was long considered to have low toxicity to non-target organisms. Notably, the precise mechanism of any toxicity in animals remains unclear; some researchers have hypothesized glyphosate might uncouple mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation at high doses, though this is disputed.

Acute toxicity: Glyphosate is practically non-toxic to mammals in acute exposure. In oral acute tests, rats showed an LD₅₀ greater than 4,320–5,000 mg/kg, meaning a very large dose is required to be lethal. For context, chemicals with such high LD₅₀ values are classified as having very low acute toxicity. Similarly low toxicity is observed via skin exposure (dermal LD₅₀ > 2,000–5,000 mg/kg in rabbits) and inhalation (4-hour LC₅₀ > 4.4 mg/L in rats). Glyphosate formulations can cause mild eye or skin irritation in some cases, largely due to surfactant additives, but glyphosate itself is not a skin sensitizer.

Chronic toxicity: Long-term animal studies have found that glyphosate’s chronic effects generally appear only at high doses. Regulatory evaluations identify no-observed-adverse-effect levels (NOAELs) on the order of tens to hundreds of mg per kg of body weight per day. For example, one review notes a NOAEL around 100 mg/kg/day in chronic studies. Based on such data, regulators have set chronic exposure limits. The U.S. EPA established a reference dose (RfD) of 1.75 mg/kg/day as an estimate of a daily lifetime exposure with no appreciable risk. European authorities have been more conservative, with the EU Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) set at 0.5 mg/kg/day, derived from a NOAEL of ~53 mg/kg/day in a 90-day animal study. In practical terms, these thresholds suggest that typical human exposures (which are in microgram per kg ranges through diet) are far below levels expected to cause harm under current safety margins. Animal feeding studies at high doses have sometimes noted mild organ effects (e.g. liver enzyme changes or kidney weight variations), but these occurred at doses many times higher than any realistic human intake. Notably, glyphosate is not a neurotoxin and did not show specific neurodevelopmental toxicity in standard tests, nor did it demonstrate reproductive or teratogenic effects at non-toxic doses in laboratory animals.

Metabolism and excretion: Glyphosate is poorly absorbed and is not significantly metabolized in animals. Studies in rats show that most of an oral dose is excreted unchanged in feces, with a smaller portion in urine. Only minimal metabolism occurs; the primary breakdown product is aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA), which is also excreted. Glyphosate’s water solubility means it does not bioaccumulate in fatty tissues. Human volunteer data and poisoning case reports likewise indicate that glyphosate is rapidly eliminated from the body largely unmetabolized. This pharmacokinetic profile – limited absorption, quick excretion, and little bioaccumulation – underpins its generally low systemic toxicity in humans when exposure is kept within regulatory limits.

Key toxicological thresholds: To summarize, glyphosate’s acute LD₅₀ in rodents is on the order of 4–5 g/kg, reflecting low acute toxicity. Chronic animal studies define NOAELs roughly in the tens of mg/kg/day, and safety factors are applied to set human exposure limits (EPA’s chronic RfD ~1.75 mg/kg/day; EU ADI 0.3–0.5 mg/kg/day). These values indicate that glyphosate’s toxicity is relatively low compared to many other pesticides, aligning with its original characterization as a “safe” herbicide. However, these conclusions are based on classical toxicological end-points; they do not preclude other subtle or long-term effects, which have been the subject of intense investigation as discussed in subsequent sections.

Cancer and Endocrine Disruption Links

One of the most contentious issues has been whether glyphosate causes cancer, especially after a major split in expert opinions emerged in the 2010s. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a WHO-affiliated body, reviewed publicly available studies and classified glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans” (Group 2A). IARC’s assessment was based on “limited” evidence of cancer in humans (noting some statistical links between glyphosate exposure and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in epidemiological studies of agricultural workers) and “sufficient” evidence in animal experiments (several high-dose feeding studies in mice showed increased incidence of malignant tumors). IARC also cited mechanistic data indicating glyphosate and its formulations can cause DNA damage and oxidative stress in lab studies. This classification as a probable carcinogen (the same category as DDT and red meat, for context) sparked global controversy and regulatory re-evaluations.

Conversely, other authoritative bodies conducted their own reviews and concluded that glyphosate is unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans under real-world exposure conditions. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), both in a 2017 evaluation and a 2020 interim registration review, upheld its stance that glyphosate is “not likely to be carcinogenic to humans” at doses relevant to human exposure. EPA scientists re-analyzed the animal data (some of which they interpreted differently from IARC) and considered exposure assessments, ultimately determining that the epidemiological evidence did not support a causal link to cancer when glyphosate is used as directed. Similar conclusions were reached by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in 2015: EFSA’s expert panel found no solid evidence of carcinogenicity and explicitly stated that glyphosate is unlikely to pose a carcinogenic hazard to humans, thus not recommending any cancer classification for the substance. In 2016, a joint meeting of experts convened by the World Health Organization (WHO) and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (the JMPR committee) likewise reported that glyphosate is “unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans” from exposure through the diet. These opposite conclusions (IARC vs. other agencies) can be explained by differing methodologies: IARC performs hazard identification (focused on intrinsic potential to cause cancer under some circumstance), whereas regulators like EPA and EFSA conduct risk assessments that factor in realistic exposure levels and weigh the totality of data, including unpublished industry studies. Nonetheless, the divergence fueled public confusion and scientific debate, with some accusing regulators of relying too heavily on industry-provided data and others arguing IARC’s evaluation gave undue weight to certain studies.

Endocrine disruption is another area of active research. Endocrine disruptors are chemicals that interfere with hormonal systems, which can lead to developmental or reproductive effects. Glyphosate is not structurally similar to known estrogenic or thyroid-disrupting chemicals, and major regulatory reviews have not found evidence that glyphosate acts as an endocrine disruptor in intact organisms. The EPA’s endocrine screening program, for example, concluded there was “no indication that glyphosate is an endocrine disruptor.” Likewise, EFSA’s 2017 assessment, conducted under new EU criteria for identifying endocrine disruptors, determined that “the weight of evidence indicates that glyphosate does not have endocrine disrupting properties” affecting estrogen, androgen or thyroid pathways. However, some independent studies in the scientific literature suggest potential endocrine-related effects, especially with glyphosate-based formulations (which include surfactants). For instance, in vitro experiments have shown high concentrations of glyphosate can weakly stimulate estrogen receptors or alter steroid production in cell lines. Animal studies at relatively high doses have reported effects like delays in puberty, changes in reproductive organ weights, or altered hormone levels. One example is a study where pregnant rats exposed to glyphosate showed offspring with signs of disrupted reproductive development and altered uterine genetics, raising concerns about multigenerational effects (Varayoud et al. 2021). These findings have led some researchers to call glyphosate a “potential endocrine disruptor,” particularly because the herbicide’s mechanism (inhibiting the shikimate pathway) is unrelated to hormones, yet subtle hormonal effects might arise secondary to other stress mechanisms.

The conflicting data on both cancer and endocrine effects have fueled intense scientific and regulatory scrutiny. It’s worth noting that formulated products (like Roundup) can be more toxic than pure glyphosate, and some studies that reported positive cancer or hormone-disruption signals used commercial formulations. This raises the question of whether observed effects are due to glyphosate itself or the combination with other ingredients. Regulators have generally maintained that the overall evidence does not confirm glyphosate as a carcinogen or endocrine disruptor at likely exposure levels, but they continue to monitor new research. Meanwhile, advocacy groups and some scientists argue that certain statistical associations (for example, higher rates of a certain cancer in heavily exposed farmers) or cellular effects justify a precautionary approach. Thus, the “glyphosate-cancer” question remains highly controversial, bridging scientific dispute and legal action (as discussed later). Below is a summary of positions from key organizations:

- IARC (WHO cancer research arm, 2015): Classified glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans” (Group 2A) based on evidence of animal carcinogenicity and genotoxicity. (IARC did not evaluate endocrine disruption.)

- U.S. EPA: In its latest assessments (2017–2020), EPA found “no risks of concern to human health” and concluded glyphosate is not likely carcinogenic at expected exposures. EPA’s review under the Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program similarly found no meaningful endocrine effects.

- EFSA (EU, 2015): Concluded glyphosate is “unlikely to pose a carcinogenic hazard to humans” and did not support classifying it as carcinogenic or mutagenic. Subsequent EU reviews also judged that glyphosate does not meet criteria as an endocrine disruptor under EU regulations.

- WHO/FAO Joint Meeting (JMPR, 2016): After re-analyzing data in the wake of IARC, this expert panel reported glyphosate is “unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans from exposure through the diet.” It also noted no evidence of genotoxicity at anticipated exposure levels. (This finding, coming from a WHO-convened committee, underscored the difference between hazard vs. risk assessment approaches within WHO itself.)

- Other agencies: The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) in 2017 agreed with EFSA, declining to classify glyphosate as a carcinogen or reproductive toxin. Health Canada and regulators in Japan, Australia, Brazil and other countries have also concluded that glyphosate is unlikely to cause cancer in humans, aligning with the EPA/EFSA viewpoint (though some have flagged data gaps or urged further study on formulated products). On the other hand, California’s EPA (OEHHA) controversially listed glyphosate under Proposition 65 as a chemical “known to the state to cause cancer” following the IARC ruling, a designation that led to contentious warning label proposals (later halted by court injunctions citing EPA’s contradictory stance).

In sum, the current scientific consensus (outside of IARC’s hazard classification) is that glyphosate by itself is not a proven human carcinogen or endocrine disruptor, particularly at the low exposure levels encountered by the general public. However, genuine uncertainties persist regarding long-term exposures, high-risk populations (like farm workers), and the effects of glyphosate in combination with other chemicals. These uncertainties continue to be investigated in toxicology and epidemiology studies worldwide.

Environmental Impact

Effects on Soil Health and Microbial Ecology

Once applied, glyphosate can bind to soil particles and is gradually broken down by soil microbes. Its environmental half-life varies, often on the order of a few weeks to months depending on conditions (soil type, climate, microbial activity). Because glyphosate targets a metabolic pathway common in bacteria and fungi (the shikimate pathway), there is concern about its influence on soil microbiomes and nutrient cycling. Research indicates that repeated glyphosate use can alter soil microbial community composition. For example, one study found that glyphosate applications reduced overall microbial richness in the soil and led to an increase in certain fungi, including potential plant pathogens. This suggests a shift in the balance of soil microorganisms – beneficial microbes may be suppressed while opportunistic fungi proliferate. Such changes could impact nutrient cycling processes like nitrogen fixation and decomposition. Indeed, some agronomic studies have reported that long-term, intensive glyphosate use correlates with lower soil organic matter and available nutrients, possibly because of reduced microbial activity in soils where plant cover (weeds) is continually eliminated. That said, not all studies find dramatic effects; many factors (like tillage practices or crop rotations) also shape soil health. Glyphosate is generally not considered persistently toxic in soil – it eventually degrades – but its “burst” of antimicrobial action upon application may disturb the soil ecosystem in the short term. There is also a chelation effect: glyphosate can bind metal ions, potentially immobilizing micronutrients in soil, which might indirectly affect plant nutrition and soil organisms. Overall, while glyphosate is often described as having negligible environmental impact compared to more persistent pesticides, accumulating evidence shows it is not neutral to soil life. Soil experts warn that heavy reliance on glyphosate-based herbicides could subtly erode soil health over time by disrupting the symbiotic microbial relationships that aid plant growth.

Impact on Pollinators and Biodiversity

A tractor applies glyphosate-based herbicide to a field. The herbicide’s widespread agricultural use has raised concerns about ecosystem effects, from the loss of wild plants to potential harm to pollinators (image: phys.org)

Though glyphosate is not an insecticide, its extensive use in agricultural and urban landscapes can affect insect populations and plant biodiversity indirectly. One prominent case is the Monarch butterfly. The decline of monarch butterflies in North America has been partly attributed to glyphosate use on genetically modified (Roundup Ready) crops, which has greatly reduced milkweed plants in and around farm fields. Milkweed is the essential host plant for monarch caterpillars. As glyphosate-based herbicides eradicated milkweed from millions of acres of cropland, monarchs lost a significant portion of their breeding habitat. This example illustrates how a herbicide can trigger ecological ripple effects through habitat modification. Similarly, when glyphosate eliminates flowering weeds in field margins or along roadsides, it can deprive bees and other pollinators of forage resources. Many wild bees rely on “weeds” like clover or dandelions for nectar; widespread herbicide spraying in rights-of-way and lawns can reduce these food sources. In response to such concerns, some farming and highway management practices now aim to create glyphosate-free refuges or timing restrictions to allow flowering before weed control.

Beyond habitat loss, direct sublethal effects on pollinators have been documented. A notable study in 2018 showed that honeybees exposed to glyphosate at environmental concentrations experienced disturbances in their gut microbiota – the communities of beneficial bacteria in the bee’s digestive tract. The researchers found that treated bees had significantly reduced levels of several core gut bacteria species, and that young worker bees exposed to glyphosate became more susceptible to infection by a pathogenic bacterium (Serratia), resulting in higher mortality. Essentially, glyphosate may be perturbing the bees’ natural gut flora (since many bee gut microbes also have the EPSP enzyme target and are sensitive to glyphosate), thereby weakening bee immunity. Other experiments have similarly observed that sublethal doses of glyphosate can reduce the abundance of beneficial gut microbes in bees, leading to immune dysregulation. While glyphosate alone doesn’t kill bees outright like an insecticide would, these findings raise alarms that chronic exposure could impair pollinator health and resilience. It’s an active area of research, as scientists try to replicate these effects in field conditions and determine what levels of exposure are problematic for pollinators.

Effects on Gut Microbiota in Animals and Humans

The impact glyphosate may have on the gut microbiome extends beyond pollinators. Because many bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract use the shikimate pathway to synthesize essential amino acids, glyphosate has the potential to disrupt gut microbial communities in other animals, including livestock and humans. A recent bioinformatics analysis found that over half of the species in the human gut microbiome are theoretically susceptible to glyphosate’s mode of action, lacking glyphosate-resistant forms of the EPSP synthase enzyme. This suggests that if glyphosate reaches the gut in sufficient concentrations, it could favor bacteria that are naturally resistant (or less affected) while suppressing others. In controlled studies on rodents, chronic low-dose glyphosate exposure has indeed been shown to alter gut flora composition. For instance, a 2021 study administered glyphosate to rats at the U.S. acceptable daily intake (1.75 mg/kg/day) and observed significant shifts in the animals’ gut microbial populations. Some beneficial bacterial groups were reduced, and metabolic changes were noted in the host, such as an increase in certain urinary metabolites (e.g. homocysteine) potentially linked to microbiome changes. Another study using a shotgun metagenomic approach confirmed that glyphosate exposure in rats can inhibit the shikimate pathway in gut microbes and lead to dysbiosis (microbial imbalance).

In humans, direct evidence is harder to obtain, but the question has drawn attention due to speculation that glyphosate residues in food might contribute to rising digestive disorders. Some researchers have hypothesized connections between glyphosate and conditions like celiac disease or general dysbiosis-related illnesses, though no causal link is proven. It remains true that detectable traces of glyphosate are found in various foods (e.g. grains, oats) and in human urine samples, indicating broad, low-level dietary exposure. Whether these trace levels can significantly affect the gut microbiota is still unclear. One study noted that glyphosate could preferentially kill certain beneficial gut bacteria in vitro, but real-life concentrations in the gut are likely much lower than those causing effects in a petri dish. As of now, regulatory bodies maintain that glyphosate is not known to harm the human gut microbiome at doses consumed in diets, pointing to the lack of clinical data on adverse gastrointestinal outcomes. Nonetheless, the topic is actively researched. Scientists stress that more in vivo studies are needed to determine if chronic dietary glyphosate intake – even at “allowable” levels – could subtly influence human gut microbial balance over time. In summary, glyphosate’s environmental and microbiological footprint is complex: it may not persist or bioaccumulate, but its biochemical effects on non-target organisms (from soil bacteria to bees to possibly gut microbes) highlight that this herbicide, while “targeted” in one sense, can have broad ecological reach.

Regulatory and Legal History

Development and Global Use

Glyphosate was first synthesized and developed as a herbicide by Monsanto Company. It was brought to market in 1974 under the trade name Roundup, after Monsanto obtained U.S. EPA approval that year. Glyphosate’s introduction revolutionized weed control due to its effectiveness on a wide range of plants and its perceived safety profile compared to earlier herbicides. In the 1990s, Monsanto further propelled glyphosate use by introducing genetically modified (GM) crops (such as Roundup Ready soy, corn, cotton, canola) that are glyphosate-tolerant, allowing farmers to spray fields to kill weeds without harming the crop. This innovation led to an exponential increase in glyphosate use worldwide. By some estimates, global usage rose from 56,000 tons in 1994 to over 825,000 tons by 2014, making glyphosate the most heavily used herbicide in history. Monsanto’s U.S. patent on glyphosate expired in 2000, after which many generic producers (including companies in China and other countries) entered the market, further driving widespread availability. Today, glyphosate-based herbicides are registered in well over 100 countries and are used not only in agriculture but also in forestry, lawn care, and industrial weed control. The compound’s ubiquity in the environment (from farm fields to urban parks) and its presence as residues in food and water have made its regulatory oversight a matter of public interest across the globe.

Regulatory Decisions, Bans, and Restrictions

Regulators in different nations have grappled with glyphosate’s approvals in light of evolving science and public concern. In the United States, glyphosate has been continuously registered since 1974 and underwent a re-registration review in 1993 with no major usage restrictions. The EPA’s most recent re-evaluation (Interim Registration Review Decision, January 2020) reaffirmed that “there are no risks of concern to human health when glyphosate is used in accordance with its current label” and did not require new mitigation measures. However, in 2022, a U.S. appellate court ordered EPA to re-examine its glyphosate assessment, citing the need to better consider potential impacts on endangered species and to address certain health study criticisms. This court decision vacated the 2020 interim approval, so EPA is currently conducting a fresh review (due by 2026). Despite this, glyphosate remains approved for use in the U.S., and no federal ban is in place. Some U.S. jurisdictions have taken their own steps – for example, a number of cities and counties (especially in California) have banned or limited glyphosate use on public lands as a precaution. California also requires a cancer warning label on glyphosate products (though, as mentioned, this is stayed pending legal proceedings).

In the European Union, glyphosate faced a major crossroads when its 15-year approval was set to expire in 2017 amidst heated debate after the IARC cancer classification. Following intense lobbying and some member state deadlock, the EU member states voted in late 2017 to renew glyphosate’s approval for 5 years instead of the typical 15, extending it to December 2022. During this period, individual countries and sub-national governments expressed differing stances. France announced an intention to phase out glyphosate for most uses within three years (President Macron targeted a ban by 2021, though full implementation lagged). Germany – home to Bayer (which acquired Monsanto) – decided to ban glyphosate in public parks and home gardens and plans a total phase-out by end of 2023. Belgium and the Netherlands prohibited glyphosate sales to home gardeners (effectively banning non-professional use). Austria went as far as passing a national ban in 2019, but it failed to take effect due to EU legal hurdles and pushback (Austria’s ban was withdrawn amid claims of procedural issues and lack of EU notification). Luxembourg did ban glyphosate in 2020, becoming the first EU country to do so, but later reversed the ban under pressure to align with EU approvals. Meanwhile, Italy and Czech Republic imposed partial restrictions (like banning use just before harvest, a practice called desiccation). Given this patchwork, the EU’s central re-approval process in 2022–2023 was closely watched. In October 2023, EU member states voted on renewal but failed to reach the required majority, leading the European Commission to extend glyphosate’s approval temporarily. Then, in December 2023, the European Commission officially re-approved glyphosate for 10 more years (until end of 2033), after the European Chemicals Agency and EFSA both once again found no clear grounds to ban it. This renewal came with some strengthened monitoring requirements but essentially permits glyphosate’s continued use in the EU, leaving specific usage restrictions (if any) to individual member states.

Outside the U.S. and EU, regulatory responses have varied: Brazil, one of the world’s largest glyphosate users, conducted its own review and in 2019 declared glyphosate posed no unacceptable risk to human health. Canada in 2019 upheld its approval of glyphosate, concluding that products are safe when used as directed, although a later 2021 analysis prompted minor label changes to protect the environment. Australia and New Zealand have maintained approvals. On the other hand, some governments have taken a harder line. In Mexico, authorities announced plans to ban glyphosate by 2024, citing precautionary health concerns and a push for organic alternatives. This policy, driven by a presidential decree, has already led to blocking some imports of glyphosate and stirred trade tensions with the U.S. Colombia banned aerial spraying of glyphosate on coca crops in 2015 due to health/environment concerns (though this was more about specific high-exposure practices), then lifted the ban in 2017 under certain conditions, then reinstated restrictions – a back-and-forth reflecting conflicting priorities of narcotics control versus public health. El Salvador similarly announced a ban but later overturned it. Vietnam became notable as one of the first Asian countries to completely ban glyphosate (in 2019, citing the IARC findings). And in a dramatic case, Sri Lanka imposed a nationwide ban on glyphosate in 2015 after some studies hypothesized a link between glyphosate and a mysterious kidney disease epidemic among farmers. That ban was later reversed in 2021 because evidence for glyphosate’s role in kidney disease remained inconclusive and because the ban had negative impacts on tea and other crop yields. Sri Lanka’s rapid ban-and-reversal is often cited as a cautionary tale in balancing precaution with agricultural necessity.

In summary, global regulatory actions on glyphosate range from continued full approvals (U.S., EU (renewed), Brazil, etc.) to targeted restrictions (especially for home use or pre-harvest use in some countries) and even to outright bans in a few nations (Vietnam, and temporarily in places like Sri Lanka). These decisions have been influenced not just by scientific assessments but also by public pressure, legal judgments, and political change. It is clear that glyphosate’s regulatory status will remain under review in many jurisdictions as new evidence emerges and as public sentiment evolves.

Monsanto, Bayer, and Legal Battles

The story of glyphosate is tightly intertwined with Monsanto’s corporate history and, since 2018, that of Bayer AG, which acquired Monsanto. Monsanto’s aggressive promotion of Roundup made glyphosate a blockbuster product, contributing billions to the company’s revenue over decades. However, it also set the stage for unprecedented legal challenges once concerns about cancer gained traction. The flashpoint was IARC’s 2015 classification of glyphosate as a probable carcinogen, which soon triggered a wave of lawsuits in the United States by individuals alleging that their cancers (specifically non-Hodgkin lymphoma, NHL) were caused by long-term exposure to Roundup. These lawsuits claimed that Monsanto knew or should have known of carcinogenic risks and failed to warn users adequately.

The first big trial was Dewayne “Lee” Johnson v. Monsanto Co. in California state court. Johnson, a former school groundskeeper, developed terminal NHL which he attributed to years of spraying Roundup and Ranger Pro (a high-concentration glyphosate formulation) in his job. In August 2018, a San Francisco jury found Monsanto liable on grounds of product liability and negligence – effectively agreeing that Roundup contributed to Johnson’s cancer – and awarded a stunning \$289 million in damages. This included \$250 million in punitive damages, reflecting the jury’s view that Monsanto acted with malice by suppressing information about risks. (The trial judge later reduced the total to \$78 million, and on appeal it was further cut to ~\$20 million, but the liability verdict was upheld.) Johnson’s case was the first to reach trial, and it set a legal precedent and public narrative. At the time, Monsanto had already been acquired by Bayer AG (the \$63 billion deal closed in June 2018), so the verdict’s impact immediately hit Bayer – its stock price dropped and it faced the prospect of massive liability.

After the Johnson win, momentum grew: Thousands of plaintiffs (eventually over 100,000) filed similar suits across the U.S. The next two trials, both in 2019, also resulted in high-profile losses for Bayer/Monsanto. A federal case in March 2019 (Edwin Hardeman v. Monsanto) ended in an ~\$80 million verdict for the plaintiff, and a California state case in May 2019 (Alva and Alberta Pilliod v. Monsanto) resulted in an eye-popping \$2 billion jury verdict (for a married couple who both had NHL), later reduced by the judge to ~\$87 million. Juries in these trials cited internal Monsanto documents (emails and reports) that, in their view, showed the company’s disregard for safety and efforts to influence scientific research and regulators – themes that will be discussed in the next section on cover-ups. Bayer vigorously appealed these verdicts, but by 2020 the litigation pressure was enormous, with tens of thousands of cases consolidated in a multidistrict proceeding.

In June 2020, Bayer announced a landmark settlement agreement: the company would pay around \$10 billion to resolve the bulk of the pending Roundup cancer lawsuits – roughly 95,000 claims – and set aside a portion of that amount for future claims. This was one of the biggest product-liability settlements in history. Bayer did not admit wrongdoing or liability, and pointed out that regulatory consensus still deemed glyphosate non-carcinogenic. But the settlement was aimed at buying peace and certainty after the string of costly trial defeats. In addition, Bayer sought court approval for a separate plan to manage any future claims via an independent scientific panel (a proposal that was rejected by a judge as it could curtail plaintiffs’ rights).

As of 2025, Bayer has paid out many of the settlement funds, though a small number of cases opted out and continued to trial or appeal. Notably, Bayer appealed Hardeman’s federal case up to the U.S. Supreme Court, seeking a ruling that federal EPA approval preempts state-law failure-to-warn claims. In mid-2022, however, the Supreme Court declined to hear the case, leaving the verdicts (and liability) intact. This means Bayer remains vulnerable to future lawsuits if new claimants come forward, especially since Roundup is still on the market without a cancer warning label. Bayer has announced that it will stop selling glyphosate-based herbicides to the U.S. residential consumer market (home & garden uses) to reduce litigation risk, substituting a different active ingredient, while continuing to sell glyphosate to farmers and professionals. Meanwhile, outside the U.S., there have been far fewer lawsuits – a few are underway in Canada and Australia. In the EU, litigation has been minimal so far, perhaps due to different liability laws and the later timing of regulatory decisions.

It’s worth emphasizing that despite these legal setbacks, Bayer (Monsanto) maintains that glyphosate is safe and that the jury decisions are not supported by science. The company points to the numerous regulatory findings of “no cancer risk” and has even run public relations campaigns to defend glyphosate’s reputation. However, internal documents disclosed in the trials (the “Monsanto Papers”) have cast doubt on some of Monsanto’s practices and credibility, strengthening the plaintiffs’ narratives. In effect, the courtroom drama has tarnished Monsanto’s legacy and become a cautionary tale in the chemical industry. For Bayer, which bought Monsanto ostensibly for its agricultural biotech assets, the acquisition became a source of enormous financial and reputational cost. Nonetheless, glyphosate-based products remain a mainstay of global agriculture, and the tug-of-war between legal judgments and regulatory approvals continues to create an unusual situation: a chemical can be declared non-carcinogenic by government scientists yet be blamed for cancer by juries awarding multi-million-dollar damages. This dichotomy underscores why glyphosate is not just a scientific and regulatory issue, but also a social and legal phenomenon.

Cover-Ups, Lobbying, and Suppression of Information

One of the darkest chapters in glyphosate’s history involves allegations that Monsanto (and later Bayer) engaged in unethical tactics to protect glyphosate’s reputation – including suppressing unfavorable research, ghostwriting scientific articles, influencing regulators, and aggressive lobbying. Many of these allegations came to light through internal company documents revealed during litigation (the “Monsanto Papers”). Below are key examples that have been documented:

- Ghostwriting of Scientific Studies: Internal emails show that Monsanto employees strategized about placing supportive research in scientific journals under the names of independent academics. In one 2015 email, a Monsanto executive (William Heydens) suggested that Monsanto scientists could “ghostwrite” parts of a favorable glyphosate safety study and have external researchers sign off on it, noting “we would be keeping the cost down by us doing the writing and they would just edit & sign their names”. This is exactly what allegedly happened with some review papers: for instance, sections of a 2000 glyphosate review by ostensibly independent authors were written by Monsanto scientists. Such ghostwriting breaches academic ethics and was meant to lend credibility to glyphosate’s safety by using the authority of neutral-seeming researchers. When these revelations emerged, several involved scientists and journals faced scrutiny. Monsanto’s internal justification was that they were providing “editorial assistance,” but plaintiffs and critics call it scientific manipulation.

- Influence over Regulatory Agencies: The Monsanto Papers also include evidence of collusion with at least one EPA official to quash investigation of glyphosate. Notably, in 2015, Jess Rowland, a deputy division director at EPA (who chaired the Cancer Assessment Review Committee on glyphosate), reportedly told a Monsanto regulator liaison that he would try to stop a review of glyphosate by another U.S. agency (the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry) and was quoted as saying, “If I can kill this I should get a medal.”. In the same email chain, a Monsanto manager wrote that Rowland “could be useful as we move forward with [the] ongoing glyphosate defense.” These communications strongly suggest that Monsanto had undue influence within the EPA, or at least a cozy relationship with an official responsible for evaluating glyphosate’s cancer risk. Rowland left the EPA in 2016, and while EPA denies any improper action, the incident has eroded confidence among some stakeholders. It also became a talking point in European debates, with Members of European Parliament referencing “EPA collusion” when criticizing assessments that cleared glyphosate.

- Suppression and Retraction of Dissenting Studies: Monsanto has been accused of orchestrating campaigns to discredit scientists whose research found glyphosate hazards. The most famous case is the Séralini affair. In 2012, French researcher Gilles-Éric Séralini published a controversial study claiming that rats fed Roundup-tolerant GM corn and low-dose Roundup over two years developed tumors and organ damage. Monsanto immediately attacked the study’s validity. According to communications revealed later, Monsanto engaged a network of scientists and allies to demand the study’s retraction, strategizing to amplify criticism that the work was “bad science”. Subsequently, the journal’s editor (who, incidentally, had previously consulted for Monsanto) did retract the paper in 2013 – an extremely unusual move that Séralini and others denounced as industry pressure. Séralini accused Monsanto of planting a former employee on the journal’s editorial board and of orchestrating a smear campaign. (The paper was later republished in another journal.) Regardless of one’s view on the study’s merits, the incident demonstrates Monsanto’s determination to suppress research that challenged glyphosate’s safety, rather than simply rebutting it with data. Internal documents also indicate Monsanto had a list of “problem” studies and scientists to monitor or refute. This kind of behavior has fueled mistrust – for example, when IARC’s 2015 glyphosate monograph came out, Monsanto (and subsequently Bayer) went to great lengths to undermine IARC’s credibility, including pressuring U.S. lawmakers to pull funding from IARC and disseminating articles to cast doubt on IARC’s process.

- Cover-up of Product Risks: Lawsuit documents revealed that Monsanto was aware that Roundup’s formulated products could be more toxic than glyphosate alone, largely due to the added surfactants that help the herbicide penetrate plants. These surfactants can make the formulation more acutely toxic (especially to cells and skin). Monsanto, however, fought against highlighting these risks. For example, plaintiffs presented evidence that Monsanto knew as early as the 1990s that one surfactant (POEA) in Roundup was highly toxic to aquatic life and could enhance glyphosate’s penetration into human skin, but the company downplayed these issues to regulators. An internal email bluntly described that the company should “not want to draw attention” to the greater toxicity of the combination. Monsanto even ghost-wrote expert reviews that asserted no significant difference in safety between glyphosate and Roundup – reviews later cited by regulators. This intent to “cover up” or minimize information about product hazards formed part of the juries’ finding of malice in the U.S. trials.

- Lobbying and Public Relations Campaigns: Glyphosate’s economic importance spurred Monsanto (and industry groups like CropLife) to mount extensive lobbying efforts worldwide. In the EU, Monsanto spent millions on lobbying the European Commission and member states during the 2017 re-approval debate. They employed PR firms to create what looked like grassroots support from farmers for glyphosate, a tactic uncovered by investigative journalists. Despite these efforts, the public controversy only grew. Notably, in 2017 the European Parliament took the extraordinary step of banning Monsanto lobbyists from its premises after Monsanto refused to send representatives to a hearing on the Monsanto Papers and glyphosate safety. MEPs stated that Monsanto showed disdain for democratic processes, and thus its access to Parliament was revoked – a rare punishment. Monsanto (now under Bayer) also lobbied U.S. officials to intervene with WHO/IARC and engaged in media campaigns to counter negative press. At times this crossed ethical lines: for instance, Monsanto contracted a consulting firm that allegedly compiled lists of influential journalists, scientists, and politicians, rating their stance on glyphosate, and in France there was a legal inquiry into whether Monsanto illegally surveilled or targeted its critics. Bayer has since apologized for that incident and pledged transparency.

In aggregate, these revelations paint a picture of a company (and later its acquirer) that placed protecting glyphosate’s commercial success above transparency and scientific integrity. Monsanto’s aggressive tactics – ghostwriting papers, meddling with regulators, attacking scientists – have been heavily criticized. It is reminiscent of the playbook used by the tobacco industry decades ago, which is a comparison no company desires. Bayer, after acquiring Monsanto, initially defended the safety of glyphosate but has also stated it is “committed to the highest principles of integrity and transparency” and that the Monsanto-era documents are being taken out of context. Nonetheless, the damage to trust is done for many observers. One outcome is that regulatory agencies, especially in Europe, have been under pressure to base evaluations only on publicly available studies and to be more stringent in reviewing industry-submitted data.

In conclusion, the glyphosate controversy has been amplified by evidence of industry misconduct. Even if the core science ultimately finds glyphosate safe or low-risk, Monsanto’s behavior – as revealed in these documents – has sown doubt and undercut public confidence in the neutrality of scientific and regulatory processes. This serves as a reminder that how science is communicated and handled can be as pivotal as the science itself in determining public acceptance.

Alternative Interpretations and Conspiratorial Frameworks

The mainstream scientific discussions about glyphosate’s risks have also been accompanied by a host of alternative theories and conspiracy-laden claims. These range from fringe scientific hypotheses to full-blown conspiracy narratives, often proliferating on the internet and social media. It is important to address these, as they influence public perception even if they lack credible evidence. Below, we summarize some common alternative claims and evaluate their validity:

- Glyphosate as the cause of various modern diseases: Some individuals argue that glyphosate exposure is behind the rise in a litany of conditions – everything from celiac disease, kidney disease, and liver ailments to autism spectrum disorder. A notable proponent of such ideas is Dr. Stephanie Seneff, an MIT computer scientist who, despite not being a toxicologist, has published hypothesis papers linking glyphosate to autism, Alzheimer’s, and more. Seneff gained notoriety for predicting that “half of all children will be autistic by 2025” due to glyphosate in the food supply – a claim widely denounced by experts as utterly unsupported (autism rates have increased, but attributing this to glyphosate is speculative and neglects genetic and diagnostic factors). This prediction was based on dubious correlations – essentially plotting autism diagnosis rates alongside glyphosate usage over time and implying causation. Correlation does not equal causation, and critics have pointed out that one could similarly correlate autism rates with organic food sales or smartphone use. No reputable studies have established a causal link between glyphosate and autism. Large epidemiological studies (for example, tracking thousands of mothers’ pesticide exposures and children’s outcomes) have not found glyphosate to be a risk factor for autism or developmental disorders. Thus, claims of an autism epidemic caused by glyphosate are considered a pseudoscientific hypothesis without credible mechanistic support or evidence from controlled studies.

- “Depopulation” and other conspiracy narratives: In the echo chambers of certain conspiracy theory groups, glyphosate is sometimes described as part of a deliberate agenda to sicken or sterilize populations. Extremist websites and influencers (often the same ones peddling anti-vaccine or chemtrail conspiracies) have labeled glyphosate a “depopulation chemical” being foisted on the world. For instance, the site NaturalNews – known for propagating health conspiracies – claims glyphosate is a “silent war on humanity” and that Monsanto/Bayer use it intentionally to reduce fertility. These theories often tie into broader narratives accusing “global elites” or specific figures (like Bill Gates or shadowy cabals) of using GMOs, vaccines, or herbicides for population control. From a factual standpoint, there is no evidence to support such conspiracy theories. Fertility rates and population trends are influenced by socio-economic factors, and while some research has examined whether chronic pesticide exposure might affect fertility, there is certainly no indication of a secret plot. In fact, regulatory bodies do assess glyphosate for potential reproductive toxicity (with studies showing no fertility harm at doses below toxic levels). The “depopulation” claim is pure conjecture, often hinging on misrepresentation of studies. For example, a recent lab study finding glyphosate in certain samples of men’s urine and semen was twisted by some outlets to claim “glyphosate found in men’s sperm, causing infertility” – a conclusion far beyond what the study showed. The scientific consensus is that environmental factors including pesticides can contribute in small ways to health issues, but pinning a large-scale phenomenon like population decrease or a chronic disease epidemic on glyphosate alone is not credible.

- Other alternative claims: Various other unproven assertions circulate in alternative health spheres. Some anti-GMO activists claim glyphosate in vaccines (traces allegedly introduced via gelatin or other components) is causing harm to children – but even if tiny residues were present, no data shows this causes any effect, and vaccine ingredients are strictly tested for safety. Others blame glyphosate for the surge in gluten intolerance and gastrointestinal issues, theorizing that wheat sprayed pre-harvest with glyphosate (a practice in some areas to desiccate crops) leads to gut inflammation. While one can argue modern farming and diet changes play a role in gut health, there is no direct evidence that glyphosate residue in wheat causes gluten sensitivity – in fact, countries that don’t use glyphosate as a desiccant have similar rates of gluten intolerance. There’s also a hypothesis by some researchers that chronic kidney disease in certain regions (like Sri Lanka or Central America) is linked to glyphosate-metal complexes in drinking water; after years of study, this remains unproven and other causes (heat stress, other toxins) seem more likely. In the pandemic era, a bizarre claim even arose suggesting glyphosate was tied to COVID-19 severity (the idea was that glyphosate weakens lungs or the immune system, exacerbating viral effects) – this was speculative and not supported by mainstream research on COVID-19.

In evaluating these alternative interpretations, the overall pattern is that they often start with a kernel of genuine concern (e.g. “could herbicides affect gut bacteria or health?” – a fair question) but then leap to extreme, all-encompassing conclusions (“glyphosate is the root of all modern diseases”) without solid evidence. These claims are typically propagated by activists or personalities with an ideological agenda (anti-chemical, anti-corporate, anti-vaccine, etc.) or by those who profit from selling “natural” alternatives. They often rely on cherry-picked studies, logical fallacies, or non-peer-reviewed reports. In contrast, authoritative sources – such as large-scale reviews by health organizations or major long-term studies – have not validated these claims. For instance, multiple rigorous studies have examined cancer rates among farmers (who use glyphosate extensively) and did not find increases in most cancers, undermining the idea of a general “poisoning” (the exception being some hints of association with NHL, which IARC noted, but even there the evidence is mixed). Similarly, the U.S. CDC tracks autism prevalence and has found correlations more closely tied to improved diagnosis and awareness, not exposure to any one environmental chemical.

To be clear, pointing out the lack of evidence for these extreme claims does not mean glyphosate is free from any health effects (we’ve discussed legitimate concerns being studied). But it’s important to separate speculation and conspiracy from science. The more outlandish notions – such as a depopulation agenda – belong to the realm of conspiracy theory rather than constructive scientific discourse. They often distract from real issues by invoking a nefarious intentional plot instead of the complex, unintentional causes that science usually finds. In the case of glyphosate, the real story involves nuanced risk assessments, subtle biological effects, corporate malfeasance, and regulatory debates – not an omnipotent scheme to harm humanity.

In conclusion, alternative and conspiratorial claims about glyphosate lack credible scientific support. They often spread through repetition in niche communities but fall apart under scrutiny. Consumers and policymakers should rely on high-quality evidence and expert risk analyses rather than sensational claims. As of 2025, the consensus is that glyphosate, while not harmless, is not the secret cause of widespread chronic diseases or population control. Its risks and impacts are being actively researched, but extraordinary claims (like causing autism epidemics or being a depopulation tool) are unsupported by the evidence and considered part of misinformation trends that have unfortunately arisen around this contentious chemical.

Sources:

- NPIC – Glyphosate Technical Fact Sheet

- U.S. EPA – Glyphosate Registration Review and Assessments

- IARC Monograph (2015) – Classification of Glyphosate

- EFSA (2015) – Conclusion on Glyphosate (Carcinogenic Hazard Unlikely)

- WHO/FAO JMPR (2016) – Statement on Glyphosate (Dietary risk unlikely)

- PNAS (Motta et al. 2018) – Glyphosate impacts on honey bee gut microbiome

- Scientific Reports (Hu et al. 2021) – Low-dose glyphosate alters rat gut microbiome

- Phys.org (AFP, Sept 20, 2023) – “Glyphosate: where is it banned or restricted?”

- Reuters (T. Bellon, 2018) – Report on Johnson trial verdict and lawsuits

- NPR (B. Chappell, 2020) – Bayer’s \$10B Roundup settlement

- U.S. Right to Know – Monsanto Papers & Emails (ghostwriting, EPA collusion)

- Retraction Watch (2017) – Monsanto campaign to retract Séralini study

- The Guardian (2017) – Monsanto lobbyists banned by European Parliament

- Natural News (as cited) – Example of depopulation conspiracy claims

Research Notes

Comprehensive Global Analysis of Glyphosate Controversies and ImpactChatGPT

I’m mapping out the comprehensive structure of the report on glyphosate, organizing it into sections like toxicological profile, cancer and endocrine disruption links, environmental impact, regulatory and legal history, cover-ups, lobbying, suppression, and alternative interpretations and conspiratorial frameworks, ensuring clarity and compliance throughout.

Searched for glyphosate toxicity thresholdsChatGPT

I found ATSDR’s toxicological profile, NPIC’s fact sheet, and an outdated EPA fact sheet. Scientific articles discuss exposure risk and glyphosate’s mechanism.

Read npic.orst.eduChatGPT

OK, let me see. The NPIC factsheet covers acute and endocrine toxicity. Double-checking its relevance due to the archived status.

Read more from npic.orst.eduChatGPT

I’m gathering info on NPIC and considering chronic toxicity, NOAEL thresholds, and avoiding duplication with endocrine disruption and carcinogenicity sections.

Read atsdr.cdc.govChatGPT

I’m crafting a detailed plan for a toxicological profile, exploring acute and chronic toxicity data, mechanisms of action, human/animal metabolism, and key thresholds. Sources include the NPIC, EPA, EFSA, and ATSDR documents.

Read more from atsdr.cdc.govChatGPT

I’m looking into the acute and chronic gastrointestinal effects in the ATSDR document, noting differences in NOAELs and LOAELs, and considering a web search to clarify formatting issues.

Searched for glyphosate NOAEL EFSA ADIChatGPT

I’m piecing together glyphosate’s use, toxicity, and food occurrence in a detailed article.

Read pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.govChatGPT

I’m gathering info on glyphosate ADIs from the EU and WHO, noting differences in safety factors and referencing EPA’s RfD for further context.

Searched for EPA glyphosate reference dose RfDChatGPT

I’m thinking through chronic and acute toxicology data, gathering reference doses and NOAELs from different agencies like EPA, EFSA, and ATSDR.

Searched for glyphosate endocrine disruptor studies EFSAChatGPT

EFSA’s 2017 report concludes glyphosate isn’t an endocrine disruptor. However, studies from 2005 and 2013 suggest endocrine-like effects, particularly at high concentrations. Hm, that’s interesting.

Read more from pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.govChatGPT

I’m considering peer-reviewed research suggesting glyphosate impacts endocrine function. EFSA found no conclusive endocrine disruptor evidence. Controversy surrounds its carcinogenic classification, with IARC suggesting it, while EPA and others conclude otherwise.

Searched for glyphosate bees microbiome studyChatGPT

I’m looking at significant PNAS studies on glyphosate’s effects on bees’ gut microbiota and immune systems, along with impactful influences on soil health.

Searched for glyphosate soil microorganisms nutrient cycling studyChatGPT

I’m gathering info from various biased sources and noting the potential insights from a PMC article and search snippet regarding glyphosate’s impact on soil.

Read more from pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Searched for glyphosate gut microbiome human studyChatGPT

I’m curious about how glyphosate might alter the human microbiome, especially since over half of its species show intrinsic sensitivity.

Read more from pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.govChatGPT

I’m focusing on research about the human microbiome’s sensitivity.

Read more from pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.govChatGPT

I’m evaluating bioinformatics analysis to pinpoint glyphosate-sensitive human gut bacteria. This review reveals the industry’s progress since 2019, emphasizing a crucial knowledge gap.

Read sciencedirect.comChatGPT

Noticing problems with an abstract link. Testing a familiar site, Nature, to see if it resolves login concerns.

Read nature.comChatGPT

I’m digging into info on the gut microbiome. Progress is steady, but it’s a bit slower than I’d like.

Read more from nature.comChatGPT

The analysis confirms glyphosate’s influence on rat and honeybee gut microbiomes, particularly inhibiting the shikimate pathway.

Read pnas.org

Searched for “Glyphosate perturbs gut microbiota of honey bees” studyChatGPT

I’m working through the TAMU PDF to gather data for the board project.

Read people.tamu.eduChatGPT

I’m piecing together the timeline for glyphosate: discovered in 1970, initially marketed in 1974, widely used post-Roundup Ready crops, patent expired in 2000, and faced various regulatory reviews.

Searched for countries banning glyphosateChatGPT

I’m trying to find the best sources to learn more, weighing the credibility and potential bias of each, and leaning towards Phys.org for a straightforward overview.

Read phys.orgChatGPT

Mapping out glyphosate bans shows varied global responses: France, Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany are enforcing bans, while Austria, Luxembourg, USA, Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, and Mexico are active in regulatory measures or discussions.

Read more from phys.orgChatGPT

Vietnam’s complete ban on a chemical is noted, likely due to IARC’s 2019 import ban.

Read more from phys.orgChatGPT

Vietnam’s ban, Sri Lanka’s reversal, and France/Germany’s discussions about the glyphosate ban progression.

Searched for Bayer glyphosate settlement 2020

Read npr.orgChatGPT

Consulting the Wisnerbaum piece to establish a clear factual timeline for the Monsanto-Bayer acquisition and its linked lawsuits.

Read more from npr.orgChatGPT

I’m noting Monsanto’s $63 billion purchase by Bayer in 2018, which brought ongoing cancer lawsuits over Roundup’s glyphosate to Bayer’s shoulders.

Searched for Dewayne Johnson glyphosate verdict 2018

Read reuters.comChatGPT

I’m piecing together major lawsuits, particularly Dewayne Johnson’s case against Monsanto, focusing on glyphosate-induced cancer, regulatory positions, and corporate resistance.

Searched for Monsanto ghostwriting glyphosate emails 2015ChatGPT

I’m working through potential research sources, like US Right to Know and WisnerBaum, to gather relevant data and insights.

Read wisnerbaum.comChatGPT

Considering an excerpt from the New York Times, March 14, 2017, regarding Monsanto’s weed killer.

Read nytimes.comChatGPT

I noticed limited access to NYT. It might be due to subscription fees or regional availability.

Read bloomberg.com

Read usrtk.orgChatGPT

I’m reviewing a research paper from Monsanto that reveals ghostwriting and checks for strategies like paying scientists to appear as authors. Additionally, industry influence over regulatory agencies stands out.

Read more from usrtk.orgChatGPT

I’m curious about Dan Jenkins’ 2015 email praising Jess Rowland for potentially halting an ATSDR study on glyphosate, linking to a broader defense strategy.

Read more from usrtk.orgChatGPT

Rowland’s statement to Monsanto indicates EPA officials colluding. Discussing suppression of conflicting studies, including the Seralini retraction caused by industry pressure.

Searched for Seralini 2012 glyphosate study retraction

Read en.wikipedia.orgChatGPT

I’m reflecting on how Wikipedia might not be the best for citing authoritative sources, yet it might briefly mention the “retraction after appointment of ex-Monsanto employee as editor.”

Read retractionwatch.comChatGPT

Documents indicate Monsanto’s effort to discredit Seralini’s study to safeguard its interests.

Read usrtk.orgChatGPT

I’m compiling sources to highlight Monsanto’s lobbying and ghostwriting, focusing on environmental and health risks. This process involves aligning the information to emphasize the industry’s efforts to counter regulation.

Searched for glyphosate lobbying EU Monsanto

Read theguardian.comChatGPT

OK, let me see. The EU Parliament banned Monsanto lobbyists in 2017, highlighting concerns about regulatory interference following allegations of undue influence on regulatory studies.

Read frontiersin.orgChatGPT

Considering pseudoscience claims linking glyphosate to gluten issues, and reviewing reputable sources to address more contentious claims, including those by Stephanie Seneff, is under deliberation. This analysis will evaluate scientific evidence and review critical perspectives.

Searched for Stephanie Seneff glyphosate autism claimChatGPT

I’m exploring Dr. Seneff’s assertions on glyphosate’s link to autism and COVID-19, trying to see if they hold up.

Read mcgill.caChatGPT

You’re engaging with various responses and reflecting on the possible actions, considering the nuances of each situation and their implications on a broader scale.

Searched for glyphosate human health claimsChatGPT

I’m noting various unverifiable claims about glyphosate, including links to autism, population control, and injected vaccines, often without credible evidence.

Searched for glyphosate depopulation conspiracyChatGPT

I’m looking into the conspiracy theory that glyphosate causes widespread health issues or infertility as part of a depopulation agenda.

Searched for glyphosate infertility conspiracyChatGPT

Evaluating glyphosate impact

Searched for glyphosate depopulation NaturalNewsChatGPT

Checking Natural News’ credibility. Alternative sources like Glenn Beck and Glenn Greenwald are being considered for more thorough analysis.

Read geneticliteracyproject.orgChatGPT

Considering GLP and Science AAAS insights.

Read science.orgChatGPT

OK, let me see. Conspiracies often emerge from anti-GMO activists and alternative health proponents, often lacking credible evidence and surfacing in non-mainstream outlets.

Read geneticliteracyproject.orgChatGPT

I’m looking into fringe theories linking glyphosate to ‘depopulation,’ which are largely unsubstantiated. Notably, NaturalNews claims it might be a depopulation chemical.

Searched for WHO FAO 2016 glyphosate carcinogenic conclusionChatGPT

I’m pulling together glyphosate evidence. Agencies like EFSA and EPA recently concluded glyphosate isn’t carcinogenic. Checking each instance ensures a comprehensive review.

Searched for EFSA 2015 glyphosate carcinogenic reportChatGPT

I’m gathering data from authoritative bodies like IARC, EPA, and EFSA, noticing varied assessments of glyphosate’s carcinogenic and endocrine effects. Progressing through evidence, focusing on highlighted agencies and controversies.

Read scx1.b-cdn.netChatGPT

OK, let me see. Adding a boom sprayer image to break up text and highlight glyphosate use is under consideration.

Read more from scx1.b-cdn.netChatGPT

I’m organizing sections to address glyphosate’s toxicological profile, health concerns, environmental impact, and regulatory matters. Progressing through these critical areas.

Read npic.orst.eduChatGPT

Noting the EPA’s 1.75 mg/kg/day chronic reference dose and the EU’s 0.5 mg/kg/day acceptable daily intake, I aim to present both regulatory thresholds without overwhelming with numbers.

I’m considering glyphosate’s metabolism in the body, particularly its excretion and formation of AMPA, to understand its persistence and potential environmental impact.

Read more from npic.orst.eduChatGPT

Glyphosate is an herbicide impacting the shikimate pathway in plants. It is minimally metabolized in mammals, explaining its low toxicity to non-target organisms.

Read more from npic.orst.eduChatGPT

I’m mapping out the organization of the document, deciding between bullet points and paragraphs. Considering major lawsuits, mappings of glyphosate’s carcinogenic potential from different agencies, and other critical details.

Read reason.comChatGPT

I’m figuring out the sections: Toxicological Profile, Cancer and Endocrine Disruption, using JMPR/WHO insights, and noting contrasting regulatory views.

Read efsa.europa.euChatGPT

I’m working through regulatory bodies assessing glyphosate’s carcinogenic potential and endocrine disruption, noting their conclusions on human risk and health effects.

Read bayer.comChatGPT

I’m curious how glyphosate in GM crops affects monarch butterflies and other pollinators. Considering its spillover into human and animal gut microbiomes, more research is essential.

Read npic.orst.eduChatGPT

Glyphosate’s journey began in 1974, spanning generics, GM crop adoption, and continues through disputes and allegations. Progressing timelines and international involvements shape its path.

Read science.orgChatGPT

I’m gathering info on various conspiracy theories, assessing their scientific validity, and considering sources to corroborate or challenge these claims.

I consulted Snopes, which found unsupported claims about one in two kids being autistic by 2025 due to glyphosate.

Read snopes.comChatGPT

I’m mapping out McGill’s text from lines 25-27, focusing on claims of exposure leading to autism using correlational graphs.

Searched for glyphosate autism graphChatGPT

I’m noting the propagation of credible and debunked claims about glyphosate, including its alleged link to ailments and conspiracy theories. The scientific consensus doesn’t support these extreme allegations.

Research completed in 10m · 46 sources

Dr Zach Bush / RESTORE product, leaky-gut caused by glyphosate