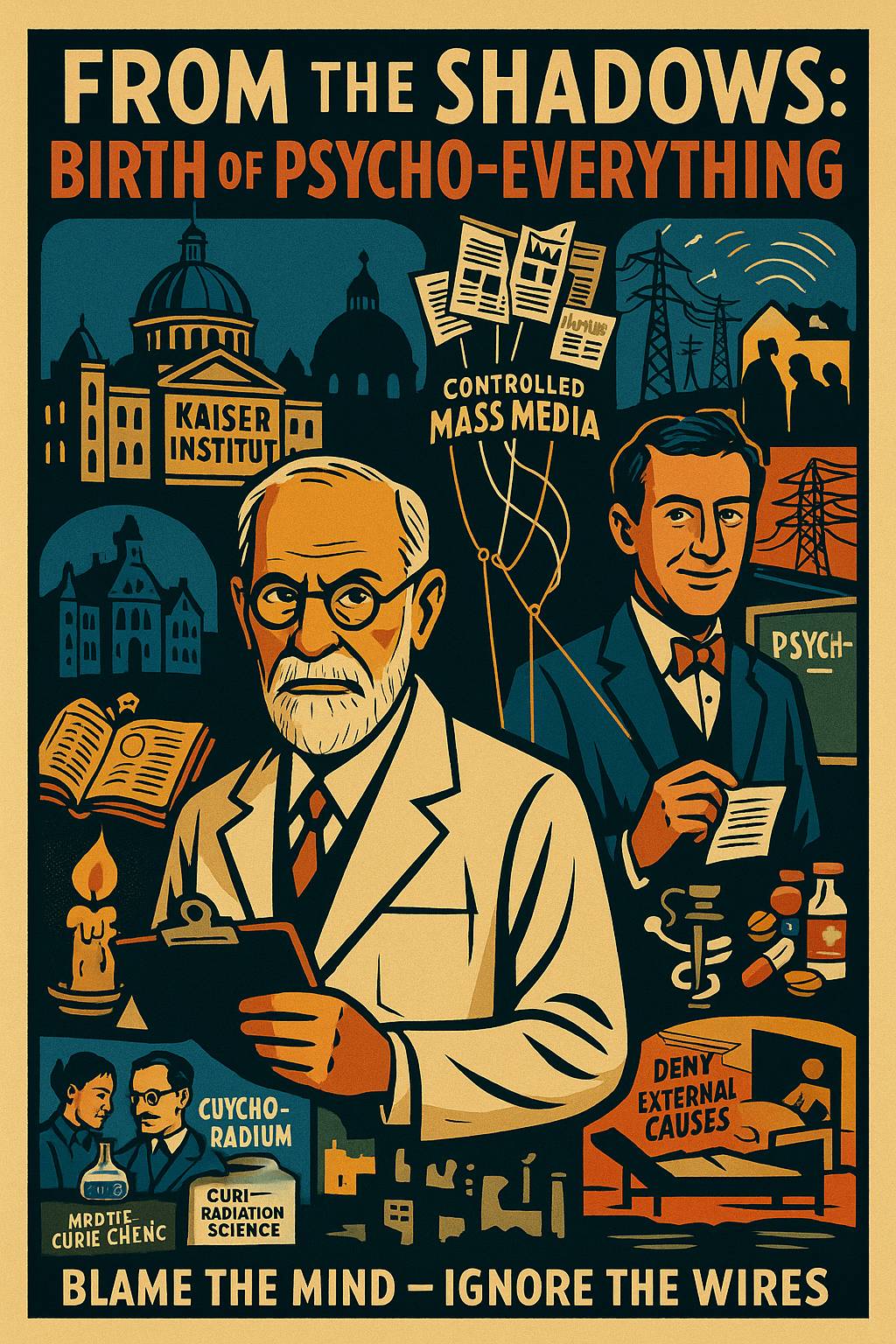

Freud’s early reputation may have been shaped by his interpretation of conditions like electrosensitivity—what was then sometimes referred to as radiesthesia—as psychological or mental disorders. Also examined is how this positioned Freud in the media (or rather how the media position Freud), the role of press and academic institutions in elevating him as a cultural authority, and specific cases or patients that may have contributed to his public prominence.

One letter near Fraud — “Big Pharma” (“harma”) based on petroleum industry, a patentable medicidinal industry was birthed alongside the mental illness paradigm championed by Freud, which largely blamed the person internally for what are in actuality massive external forces.

Freud’s Get-Go: Reframing Physical Illness as Psychological

From Neurology to Psychoanalysis: Freud’s Early Career Context

Sigmund Freud began his career as a neurologist in the late 19th century, a time when many mysterious “nervous” ailments confounded medicine. After studying with Jean‐Martin Charcot in Paris (where hysteria was being intensively researched), Freud returned to Vienna and collaborated with Josef Breuer on treating hysterical patients simplypsychology.org simplypsychology.org. In their landmark book Studies on Hysteria (1895), Breuer and Freud argued that hysteria – which presented with very real physical symptoms like paralysis, coughs, or sensory loss – could originate from hidden mental traumas rather than organic diseasesimplypsychology.org. The famous case of “Anna O.” illustrated this new approach: although Anna O. suffered blindness, limb paralysis, and hallucinations with no clear physical cause, Breuer reported that her symptoms improved once she spoke about buried emotional experiences (“the talking cure”) simplypsychology.org simplypsychology.org. By reframing such perplexing physical conditions as products of the mind, Freud helped establish the field of psychoanalysis – a radical shift from the purely somatic (body-based) theories of illness that had dominated neurology.

[Meanwhile, as later shown in Arthur Firstenberg’s book INVISIBLE RAINBOW, man-made electromagnetic radiation for the first time in acknowledged history began its first large-scale, powerful submergings of swatchs of humanity, resulting in very real pandemics, illnesses and diseases.]

Freud’s early positioning in academia was somewhat unconventional. He had trained in clinical neuroscience and even published on topics like aphasia, but his interests moved toward the intangible realm of the psyche. In 1885–86 he held a traveling fellowship with Charcot, then returned to Vienna to open a private practice in “nervous” disorders. Lacking a senior academic post, Freud initially worked outside the university mainstream. (He was not made a professor in Vienna until 1902, and even then only in an honorary capacity.) Instead, he built his reputation through published case studies, theoretical papers, and a small circle of like-minded colleagues. This semi-outsider status did not prevent him from pursuing bold ideas. In fact, Freud acknowledged that many peers thought him a monomaniac for obsessively studying the neuroses, yet he felt he had “touched on one of the great secrets of nature” encyclopedia.com. His willingness to challenge orthodox explanations of baffling conditions would prove key to his rise.

Interpreting Physical Symptoms as Mental Disorders

A cornerstone of Freud’s early work was the idea that physical symptoms with no evident lesion – paralyses, pains, coughs, fainting spells, etc. – could be psychogenic (originating in the mind). Hysteria was the classic example: the patient’s blindness or limb paralysis was real, but Freud argued it stemmed from repressed emotional conflicts rather than a tumor or nerve damage. By treating these symptoms with psychological methods (hypnosis or free association) and uncovering the underlying emotional trauma, Freud and Breuer claimed success in curing patients like Anna O. simplypsychology.org simplypsychology.org. This reclassification of a traditionally “medical” disorder (hysteria had long been thought to have a uterine or neurological cause) into a psychological one earned Freud considerable attention. It positioned him as a pioneer who could explain what other physicians could not. Indeed, the Studies on Hysteria cases were published not just to help patients, but to demonstrate the power of the cathartic method and stake a claim in the scientific debate. Freud later admitted that the book’s publication aimed to show their method’s efficacy “primarily to demonstrate that the cathartic method…preceded the research published by Pierre Janet” – essentially asserting priority in discovering this new approach encyclopedia.com. This bold reframing of hysteria as a psychological disorder helped set Freud apart in the medical community.

Another important instance of Freud interpreting vague physical problems as psychological was with the diffuse condition known as neurasthenia. In the late 1800s, neurasthenia (a syndrome of “weak nerves” characterized by fatigue, dizziness, palpitations, and myriad other complaints) was a popular diagnosis in Europe and America thepowercouple.ca thepowercouple.ca. Some physicians even speculated that modern technology was to blame; for example, in 1885 the German psychiatrist Rudolf Arndt provocatively suggested that “electro-sensitivity is characteristic of high-grade neurasthenia,” linking patients’ nervous exhaustion to the burgeoning electrical environment of the Industrial Age thepowercouple.ca. Freud took a very different path. In a key 1895 paper, “On the Grounds for Detaching a Particular Syndrome from Neurasthenia under the Description ‘Anxiety Neurosis’,” he argued that many cases labeled neurasthenia were actually a distinct anxiety disorder with psychological and sexual origins encyclopedia.com. Freud proposed that symptoms like heart palpitations, tremors, sweating, dizziness, insomnia, and gastrointestinal troubles – today we might call them panic attack or somatic anxiety symptoms – formed a syndrome he named “anxiety neurosis.” Crucially, he theorized these symptoms did not come from electrical currents, overwork, or other external physical causes, but from internal psychic tensions, particularly disturbances of sexual energy (“libido”) that were not discharged normally encyclopedia.com encyclopedia.com. In Freud’s view, a young woman’s panic attacks might stem from pent-up sexual anxiety (e.g. frustration or trauma), not from telegraph wires or environmental toxins.

Freud’s reclassification of many neurasthenic symptoms as Anxietyneurose (anxiety neurosis) had a significant impact. It effectively redirected doctors’ attention away from potential physical or environmental explanations toward psychological ones. As one historian put it, “Freud ended the search for a physical cause of neurasthenia by reclassifying it as a mental disease” ia601808.us.archive.org. After Freud’s intervention, the broad old diagnosis of neurasthenia began to fragment: what could not be explained by lesions or laboratory tests was now often considered a neurotic disorder of the mind. In fact, Freud’s 1895 paper won him considerable recognition among his peers – the newly identified anxiety neurosis syndrome became a topic of lively discussion at neuropsychiatric congresses in the early 1900s encyclopedia.com. Many doctors were intrigued by this fresh framework that made sense of puzzling “modern” ailments. By arguing that a whole range of common symptoms – from vertigo and palpitations to numbness and fainting spells – were manifestations of repressed psychic conflict, Freud enhanced his credibility as a bold theoretician. This reframing “earned Freud considerable recognition” and marked his emergence as an authority on the neurosesencyclopedia.com.

Notably, Freud did not explicitly write about electrical or radio-wave sensitivity (often called radiesthesia in later eras) in his early case studies – such terms were not yet common in medical literature. However, the symptoms he addressed under anxiety neurosis closely mirrored what some 20th-century patients would describe as “electromagnetic hypersensitivity.” A modern commentator observes that “the symptoms listed by Freud [for anxiety neurosis]…will be familiar to every doctor, every ‘anxiety’ patient, and every person with electrical sensitivity” ia601808.us.archive.org. Freud’s catalogue included irritability, heart arrhythmias and chest pains, shortness of breath (asthma), sweating, trembling, extreme hunger, diarrhea, vertigo, flushing or chills, tingling, insomnia, nausea, frequent urination, and rheumatic pains ia601808.us.archive.org ia601808.us.archive.org – a comprehensive array of physical complaints that overlap heavily with what individuals today might attribute to Wi-Fi or cell tower exposure. In Freud’s time, these vague maladies were attributed either to “weak nerves” or to psychological causes; Freud forcefully pushed the latter interpretation. By doing so, he helped establish the psychogenic model for medically unexplained symptoms. This certainly boosted Freud’s standing in psychiatry – he was carving order out of chaos – but it also had a lasting side effect: it marginalized inquiry into physical explanations. As one critic later summarized, “All of the cases of neurasthenia, which were concerned with the nerves of the body, were now classified as a mental disease…environmental illness caused by a toxic environment [was not given] much credence due to Freud, who blamed its symptoms on…disordered thoughts” thepowercouple.ca. In other words, Freud’s early success in redefining ailments as psychological contributed to a prevailing attitude (still influential in medicine for decades) that if no organic pathology is obvious, then the problem must be “all in the mind.”

Neurasthenia, Radiesthesia and Freud’s Approach

Although Freud himself did not use the term “electrosensitivity,” it is worth examining how his approach differed from those who did consider electrical or radiative influences on health. The concept of radiesthesia (sensitivity to radiation or electromagnetic forces) was a fringe idea at the turn of the 20th century – for example, some dowsers and occultists claimed certain people could feel invisible “rays.” A few orthodox physicians also speculated about electricity’s effects: as mentioned, Dr. Rudolf Arndt linked neurasthenic anxiety to the electrification of daily life, and American neurologist George Beard (who coined “neurasthenia” in 1869) suggested that modern innovations like the telegraph, telephone and railway might be overwhelming people’s nerves thepowercouple.ca thepowercouple.ca. This was an era when electricity was new and mysterious; “railway spine” (traumatic shock after train accidents) and even “telegraphist’s nerve fatigue” were discussed in medical journals. Freud, however, remained firmly skeptical that external physical energies were causing neuroses. He was a product of the late Victorian shift from vitalism to psychology – instead of unseen physical forces, he focused on unseen mental forces.

Freud’s anxiety neurosis theory explicitly challenged the need to find an external toxin or stimulus to explain patients’ symptoms. He argued that the cause lay in internal psychic tension – in particular, a failure to properly “discharge” sexual excitation. In his 1894–95 writings he asserted that “no neurasthenia or analogous neurosis exists without a disturbance of the sexual function” encyclopedia.com. Thus, a patient’s dizzy spells or tachycardia were, in Freud’s view, likely rooted in repressed sexual anxiety or frustration (what he called an “actual neurosis”), not in telegraph wires humming outside their window. This was a dramatic reframing: it turned attention away from the environment and squarely onto personal history and emotional life.

It can be argued that Freud’s stance helped solidify his credibility because it aligned with a broader trend in medicine to deemphasize nebulous environmental diagnoses. By the early 20th century, many physicians were growing impatient with catch-all concepts like neurasthenia; Freud offered a more structured nosology (hysteria, anxiety neurosis, obsessional neurosis, etc.) grounded in nascent psychoanalytic theory. His framework gained enough traction that, in the West, neurasthenia essentially “died out” as a formal diagnosis – “anxiety disorders” and other psychoanalytic terms took its place ia601808.us.archive.org. Interestingly, in other parts of the world the idea of neurasthenia persisted. Russian and Soviet doctors, for instance, largely rejected Freud’s redefinition; throughout the 20th century, Russian medicine continued to diagnose neurasthenia and investigated various environmental causes, including “electricity and electromagnetic radiation in their various forms,” as contributing factors ia601808.us.archive.org. In the Soviet Union, where materialist science was favored, Freud’s libido-centric theories were viewed with suspicion, and research into things like the biological impacts of radio waves on the nervous system had more room to continue. But in Freud’s sphere of influence (Western Europe and later the U.S.), his psychogenic explanations carried the day. This had a lasting influence: complaints of illness from electricity or other modern technologies tended to be seen as psychosomatic or “neurotic” for many decades, reflecting Freud’s legacy of privileging psyche over physics in the clinic thepowercouple.cathepowercouple.ca.

In summary, Freud did not specifically analyze “electromagnetic sensitivity” in any patient – the term and concept as we know it emerged later – but he did play a role in transforming how such ambiguous syndromes were viewed. Conditions that some contemporaries attributed to physical forces (be it electricity, “bad air,” or germs) were often reinterpreted by Freud as manifestations of mental conflict. This reframing boosted his standing as an innovator who could explain the unexplainable. At the same time, it generated debate about whether he was dismissing legitimate physical etiologies. Freud’s early rise must be understood in that context: he offered a compelling new narrative (mind over matter) that won him both ardent followers and skeptical critics.

Early Recognition, Press Coverage, and Popularization

Freud’s innovative ideas initially spread through medical circles via papers and congresses, but before long they reached the broader public – thanks in part to strategic events and media coverage. A pivotal moment was 1909, when G. Stanley Hall invited Freud (along with Carl Jung and other colleagues) to Clark University in Massachusetts for a conference marking the university’s 20th anniversary. This was Freud’s first and only trip to the United States, and it effectively introduced psychoanalysis to America in a very public way commons.clarku.edu. Freud delivered a series of five lectures (in German, with Jung translating) about the origins and evolution of psychoanalysis. The event was widely covered by the press: newspapers from the Boston Globe to the New York Evening Post and wire services reported on the “noted Viennese Professor Freud” explaining his dream theory and the treatment of hysteria commons.clarku.edu. These press clippings (preserved in Clark University’s archives) show that the American media took considerable interest – some reports were respectful explanations of Freud’s ideas, while others were more sensational, playing up the sexual aspects of his theory to intrigue readers. In any case, the Clark University lectures gave Freud and his ideas a burst of popular visibility that extended beyond the academic world. One contemporary noted that after 1909, Freud’s name and the concept of the unconscious started to become familiar even to laypersons in the U.S. psychiatric milieu psychiatryonline.org.

Over the 1910s and 1920s, Freud’s works were translated into multiple languages (English translations by A.A. Brill and others began appearing by 1910–1912). Influential publishers and intellectuals helped disseminate his thought. For example, in England, Freud’s writings were issued by the Hogarth Press (run by Leonard and Virginia Woolf) and promoted by the emerging British Psycho-Analytical Society. In the United States, journals like the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease published monographs of Freud’s key essays, and prominent psychologists such as William James and Adolf Meyer took note of his work. Even before mainstream acceptance, this network of translators, publishers and sympathetic scholars effectively “hyped” Freud’s ideas by making them accessible and sparking discussion across Europe and America. By the 1920s, psychoanalysis had an air of avant-garde chic in some circles, and Freud was gaining a public reputation as a bold explorer of the human mind.

The popular press also continued to build Freud’s profile. A milestone of sorts came in 1924, when Time magazine in the U.S. put Sigmund Freud on its cover – a clear sign he had become a figure of wide interest commons.wikimedia.org. The cover story (October 27, 1924) introduced Freud’s life and theories to general readers, casting him as a revolutionary thinker in mental health content.time.com. Such coverage cemented his status as the authority on the unconscious mind in the public imagination. Around the same time, newspaper and magazine articles on topics like “Freudian meaning of dreams” or “the new psychoanalysis” proliferated. Some were serious interviews or essays in venues like The New York Times or Atlantic Monthly; others were lighthearted or tongue-in-cheek pieces referencing Freud to explain fashionable fads or the behavior of celebrities. The net effect was that Freud’s name entered everyday language – terms like “Freudian slip” or “Oedipus complex” became widely recognized buzzwords, even if often misused or simplified.

Institutions and influential individuals actively promoted Freud’s ideas as well. Apart from academia (where dedicated psychoanalytic institutes and training programs were being established in the 1920s), there were cultural and media figures who brought Freudian concepts to new domains. One indirect but significant promoter was Freud’s own nephew, Edward Bernays, an early public relations pioneer. Bernays applied Freud’s theories of unconscious drives to develop modern advertising and PR techniques, essentially popularizing the notion that hidden irrational urges drive consumer behavior medium.com westviewnews.org. Although Freud himself kept a distance from commercialism, Bernays’ success in propaganda and marketing (detailed in his 1928 book Propaganda) indirectly spread Freud’s fame by showing the practical power of his ideas in mass culture westviewnews.org. In a different vein, Freud’s intellectual disciples such as Ernest Jones and Carl Jung gave public lectures and wrote accessible essays on psychoanalysis, further broadcasting Freud’s theoretical empire. For instance, in 1910 the International Psychoanalytic Association was founded, and its members often engaged with the press and lay audiences; by the 1920s there were psychoanalytic conferences attracting journalists, and even clinics offering Freudian therapy to the public in cities like Berlin and London.

By the late 1920s, Sigmund Freud had become something of a cultural icon, not just a doctor. This status was acknowledged both in honors and in popular media. In 1930, the city of Frankfurt awarded Freud the Goethe Prize, one of Germany’s highest literary honors, explicitly recognizing the profound impact of his ideas on society and culture jta.orgjta.org. (The prize committee praised Freud’s “creative genius” for having “fructified an entire generation” and spread European science worldwide jta.org.) Around that same time, Hollywood showed interest in Freud – notably, in 1925 the movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn traveled to Vienna to offer Freud $100,000 to consult on a film about great love stories, hoping to inject psychoanalytic insight into entertainment scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk. Freud, who was skeptical of American mass culture, famously refused to meet Goldwyn scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk, yet the very invitation demonstrated how prominent he had become. A few years later, in 1926, the German director G.W. Pabst produced Secrets of a Soul, a feature film about psychoanalysis (with Freud’s associates advising, since Freud again declined involvement)scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk. By the 1930s and 1940s, plotlines involving Freudian psychoanalysts were staples of cinema on both sides of the Atlantic scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk. All of this contributed to Freud’s growing mystique as the oracle of the unconscious. Whether one accepted his actual doctrines or not, “Freud” had become a household name and a symbol of deep insight into human behavior.

Promotion, Hype, and the Making of a Cultural Icon

Throughout these years, many publishers, journalists, and institutions played a role in amplifying Freud’s profile. Influential publishing houses ensured that Freud’s works and those of his followers were widely available. The Vienna Psychoanalytic Society (founded in 1902) started its own journal and yearbook, giving Freud’s circle a platform to promote case reports and theory. In 1913, the International Journal of Psychoanalysis was launched (with Ernest Jones as a key editor) to spread Freudian thought globally. Such institutional backing helped legitimize psychoanalysis and kept Freud’s name in professional discourse. Meanwhile, popular publishers brought psychoanalytic ideas to general readers – for example, Freud’s Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis (a series of talks given in 1915–1917) were published in book form and became an international bestseller in the 1920s. The press sometimes exaggerated or oversimplified Freud’s ideas for sensation, but even that “hype” contributed to his fame. Tabloids might blare headlines about “Freud’s theory that sons hate their fathers” or the scandalous emphasis on sexuality, which, despite being distortions, piqued public curiosity.

Journalists, too, had a hand in shaping Freud’s image. Some wrote admiring profiles portraying him as a genius unlocking the secrets of dreams; others were critical or even mocking. The diversity of coverage actually kept Freud in the public eye as a controversial figure worth knowing about. Notably, as early as 1910, The New York Times ran pieces about Freud’s dream theory and the “new psychology,” and by the 1920s it was publishing articles on the latest Freudian concepts on a regular basis. High-profile writers and intellectuals also engaged with Freud’s theories, sometimes in popular essays or books. For instance, H.G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw discussed Freud in their writings, and the surrealist artists (like Salvador Dalí) touted Freud’s influence on their art. Every such mention outside clinical circles enhanced Freud’s status as more than a doctor – as a thinker influencing art, literature, and even everyday life. By 1932, one could find references to Freud in venues as disparate as literary criticism, political discourse, and comic strips. As one retrospective put it, even where Freud’s specific claims were debated or debunked, “no one could dispute the pervasive influence of his spirit…his work has permeated almost every aspect of modern culture,” from high art to “dirty jokes,” from serious novels to Hollywood movies independent.co.ukindependent.co.uk. In short, Freud had been successfully promoted (directly and indirectly) into a worldwide cultural phenomenon.

It’s important to note that Freud’s elevation to cultural icon status was not solely organic – there was conscious promotion by devoted followers. Disciples like Ernest Jones in England and Princess Marie Bonaparte in France worked hard to secure Freud’s legacy and spread his influence. Jones, for example, wrote many articles and eventually a multi-volume Freud biography that cast Freud in a heroic light. Publishers such as Max Schur and James Strachey labored to produce the Standard Edition of Freud’s works in English, ensuring that future generations could read him. Even institutions like the BBC gave Freud airtime: in 1938, upon Freud’s 80th birthday and his escape from Nazi-occupied Austria to London, the BBC broadcast a radio address by Freud (one of his only recorded speeches), treating him as an esteemed sage of the age. Such institutional acknowledgments further enshrined Freud as an authoritative figure in psychology.

Controversies and Critical Discourse

While Freud’s reinterpretation of various conditions won him acclaim, it also sparked significant controversy from the start. Many in the medical community were uneasy with how readily Freud explained physical symptoms as psychological. In the 1890s, some physicians accepted Freud’s concept of anxiety neurosis, but rejected his insistence on a purely sexual cause. A respected Munich psychiatrist, Leopold Löwenfeld, criticized Freud’s 1895 paper, arguing that Freud had not proven every case of anxiety was rooted in sexual dysfunction encyclopedia.com. Freud, normally averse to public polemics, felt compelled to publish a rebuttal in which he clarified his position (allowing that factors like heredity or overwork could play a role, but maintaining that a specific sexual etiology was the key) encyclopedia.com encyclopedia.com. This exchange highlighted a broader skepticism: many doctors were willing to grant that Freud had identified a real syndrome (“anxiety neurosis”), yet “the ideas of Freud and some other authors on the sexual origin of the neuroses [were] far from accepted by the majority of doctors,” as Paul Hartenberg wrote in 1902 encyclopedia.com. To make the concept more palatable, Hartenberg and others suggested broadening the cause to include “overwork and exhaustion of the organic,” rather than Freud’s exclusive focus on sexual factors encyclopedia.com. Essentially, there was early pushback that Freud was over-psychologizing and oversexualizing conditions that might also have physical or multifactorial origins.

Another major controversy of Freud’s early career was the famous reversal of his “seduction theory.” In 1896 Freud had boldly proposed that at the root of hysteria lay actual sexual abuse (seductions) in childhood – a shocking claim that many contemporaries found implausible or scandalous thecrimson.com. Freud initially believed his hysterical patients’ accounts of early sexual traumas were real; however, this theory met with intense professional skepticism and even ostracism thecrimson.com. Within a few years, Freud recanted, formulating instead that these patients’ stories often represented unconscious fantasies (wishes or imaginings) rather than literal events. Critics then and now have debated Freud’s motives for abandoning the seduction theory. One interpretation (advanced by scholar Jeffrey Masson) is that Freud caved to social pressure – that he “gradually discarded his new theory in order to end his professional isolation,” effectively choosing the more acceptable explanation (internal fantasies like the Oedipus complex) over the disturbing reality of rampant child abuse thecrimson.com. Masson argues that this shift “away from the real world” toward an inner, imagined drama was a turning point that traded truth for credibility thecrimson.com. Freud’s defenders, on the other hand, claim he revised the theory because he realized his patients’ reports were not always reliable memories and that the unconscious mind could create symbolic fictions. Regardless of who is right, the episode certainly generated “critical discourse” about Freud’s methodology and willingness to fit evidence to theory. It remains one of the early controversies that shadowed Freud’s reputation: some accused him of intellectual dishonesty or at least of letting the politics of respectability influence his scientific conclusions thecrimson.com thecrimson.com.

Beyond theoretical disputes, Freud was criticized for specific case handling – especially where physical illness and psychological interpretation intersected. A notorious example is the case of Emma Eckstein, one of Freud’s patients in the 1890s who suffered from stomach pains and depression. Freud, following the advice of his friend Wilhelm Fliess, had Eckstein undergo an experimental nasal surgery (based on Fliess’s odd notion of a link between the nose and genitals) thecrimson.com. The operation went awry: Fliess left half a meter of gauze in Eckstein’s nasal cavity, causing a severe infection and hemorrhage that nearly killed her thecrimson.com. Another doctor had to emergency-extract the surgical gauze, and a “flood of blood” ensued as Freud himself described thecrimson.com. In the aftermath, Freud was distraught – but remarkably, he wrote to Fliess that Eckstein’s frightening bleeding episodes had been “hysterical” manifestations of her longing for Freud’s attention thecrimson.com. In other words, Freud reinterpreted the very real medical crisis as partly a product of the patient’s psyche (“an unconscious wish to entice me to come there”) thecrimson.com. He concluded that once the physical crisis was handled, her continuing minor bleeds might be psychologically driven by desire. To later critics, this was an alarming example of Freud explaining away a physical injury with a psychic explanation. As one commentator put it, “The powerful tool that Freud was discovering – the psychological explanation of physical illness – was being pressed into service to exculpate his own dubious behavior and that of his friend” thecrimson.com. This incident remained hidden until Freud’s correspondence was published decades later, but once revealed (first by Freud’s biographer Ernest Jones, and later by Masson and others), it fueled arguments that Freud sometimes went too far in psychologizing, possibly to defend his theories or personal ego. The Eckstein case has since become a staple in Freud critiques, illustrating the potential dangers of dismissing legitimate physical causes as “merely” neurotic. It underscores that from early on, there was controversy not just around Freud’s ideas, but around the ethical and diagnostic judgment behind his casework.

Additionally, as Freud’s ideas gained cultural popularity, a backlash developed in some quarters. By the 1920s and 1930s, even as Freudian jargon pervaded the arts and popular media, many medical professionals (especially in the burgeoning field of psychiatry) and academics (such as behaviorist psychologists) were openly skeptical of Freud’s scientific rigor. Some critics derided psychoanalysis as a kind of cult or pseudoscience – too reliant on unobservable notions and unverified clinical anecdotes. For example, the prominent American psychologist G. Stanley Hall (who had invited Freud in 1909) later expressed ambivalence about the more extreme claims of Freudians. Others pointed out that Freud’s theories were unfalsifiable and that his therapy results were hard to objectively measure. In the 1940s, the tide of academic opinion turned further against Freud in the English-speaking world; figures like psychiatrist Frank Sulloway and others would label Freudian psychoanalysis a “dogma” that had captured institutions and even Hollywood’s imagination, but lacked empirical support ia601808.us.archive.org. Nonetheless, during Freud’s lifetime and the years immediately after, such criticism was often drowned out by the near adulation he received as a pioneer. Even detractors had to acknowledge his influence. An article in The Independent (UK) in 2000 noted that while Freud’s specific clinical claims had come under “heavy fire,” the “pervasive influence” of his ideas on modern culture was indisputable independent.co.uk. This dual legacy – Freud as revered trailblazer and Freud as controversial theorist – was born in those early decades of the 20th century when he rose to prominence through a mix of intellectual innovation, savvy self-promotion (and promotion by allies), and intense public fascination.

Conclusion

Sigmund Freud’s early rise to prominence was deeply entwined with his bold reinterpretations of mysterious ailments from the physical domain into the psychological. By asserting that conditions like hysteria and neurasthenia were not due to electrical currents or hidden lesions but rather to conflicts and anxieties within the mind, Freud positioned himself at the forefront of a paradigm shift in medicine thepowercouple.ca encyclopedia.com. This reframing won him both credibility and notoriety. It gave Freud a distinctive authority in the eyes of many physicians desperate for new approaches to intractable problems – his syndrome of “anxiety neurosis,” for example, was taken up and discussed by leading neurologists and psychiatrists, bringing him recognition and esteem encyclopedia.com. At the same time, it attracted skepticism and criticism from those who felt he went too far in minimizing physical factors encyclopedia.com thecrimson.com. Freud navigated these currents shrewdly, adjusting some theories (as seen in the seduction theory pivot) to maintain influence, all the while remaining a provocateur who was not afraid to challenge the medical status quo.

Beyond the clinic and lecture hall, Freud’s ascent was amplified by timely institutional support and media exposure. The early 20th-century press played a crucial role in transforming Freud from an obscure Viennese doctor into an international figure. High-profile events like the Clark University lectures in 1909 brought Freud to the front page of newspapers commons.clarku.edu commons.clarku.edu, and ongoing engagement by journalists and publishers kept his work in the public consciousness. Influential publishers (academic and popular alike) ensured that Freud’s writings were widely read, and acolytes in various countries acted as evangelists for his ideas. By the 1920s, Freud had become not just a man but a myth – celebrated as the discoverer of the unconscious, caricatured as the apostle of sex, consulted (directly or indirectly) for insights into everything from advertising to art. Honors like the 1930 Goethe Prize validated Freud’s cultural importance, with dignitaries praising how his “genius fructified a generation” and spread European thought globally jta.org. And yet, alongside the acclaim, a critical discourse persisted – in academic journals, in rival therapeutic schools, and in the court of public opinion – questioning his evidence and the perhaps overzealous application of his theories (especially to explain away physical ills).

In exploring Freud’s early career, one finds a complex interplay of innovation, promotion, and controversy. He gained credibility among many medical peers precisely by offering a new lens on ambiguous illnesses like radiesthetic sensitivities or neurasthenic fatigue – even if he did so by essentially declaring those conditions psychogenic. This credibility was further bolstered by savvy use of case studies (such as Anna O. for hysteria) to dramatize his success encyclopedia.com. At the same time, those cases and explanations were scrutinized and sometimes challenged as incomplete or self-serving. The broader context shows that Freud’s rise was not an isolated phenomenon: it coincided with a moment in Western culture eager for heroes of science and mind, and Freud fit the bill. The press hyped his most sensational ideas, institutions gave him platforms and prizes, and a fascinated public made him into a cultural icon – all while debates raged around him.

Ultimately, Freud’s early prominence was a product of both his bold reimagining of mental illness and the world’s readiness to embrace a new narrative about human behavior. By recasting enigmatic physical complaints as diseases of the mind, Freud did more than advance medicine; he tapped into a narrative of personal inner struggle that resonated far and wide. It made him famous, it made him influential, and it also made him controversial. As one observer aptly noted on the centenary of The Interpretation of Dreams, even after a century of criticism Freud’s ideas “still pervade modern culture” in forms both profound and trivial independent.co.uk. Few figures in medical history have ridden the twin currents of scientific innovation and media-driven popularization as effectively as Freud did. His early career is a testament to how reframing a problem in a compelling new way – here, treating electrosensitivities and mysterious pains as psychological – can elevate a practitioner’s status, especially when that reframing is carried to the public by powerful storytelling and institutional endorsement. Freud became the authoritative voice of psychiatry in his era, and a cultural icon beyond, precisely through this synergy of groundbreaking theory, promotion by allies and press, and the controversies that kept his name in circulation. The story of Freud’s rise illustrates how medical ideas gain prominence not just on their scientific merit, but through the social and media forces that shape their reception.

Sources:

- Freud, S. (1895). On the Grounds for Detaching a Particular Syndrome from Neurasthenia under the Description “Anxiety Neurosis.” Discussed in encyclopedia.comencyclopedia.com. (Standard Edition, Vol. 3, pp. 85–115).

- Studies on Hysteria (Breuer & Freud, 1895), case of Anna O. as summarized in simplypsychology.orgencyclopedia.com.

- Arndt, R. (1885). Discussion of neurasthenia and electrical sensitivitythepowercouple.ca.

- The Invisible Rainbow: A History of Electricity and Life – Firstenberg, A. (2017), which critiques Freud’s impact on the understanding of neurastheniaia601808.us.archive.orgia601808.us.archive.org.

- Encyclopedia.com – “Neurasthenia and Anxiety Neurosis”encyclopedia.comencyclopedia.com.

- Clark University Archives – accounts of Freud’s 1909 lectures and press coveragecommons.clarku.educommons.clarku.edu.

- Time Magazine cover story on Freud (Oct. 27, 1924)commons.wikimedia.org.

- National Science and Media Museum – “Freud and cinema” (on Goldwyn’s 1925 offer)scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk.

- The Independent (Kevin Jackson, 2000) – on Freud’s cultural influenceindependent.co.uk.

- Jewish Telegraphic Agency report (1930) – Goethe Prize award to Freudjta.org.

- Masson, J. (1984). The Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory – as discussed in Harvard Crimson reviewthecrimson.comthecrimson.com.

- Details of Emma Eckstein case from Freud-Fliess correspondence, cited in Masson and othersthecrimson.comthecrimson.comthecrimson.com.

- Hartenberg, P. (1902). La névrose d’angoisse – noting broader etiologies vs. Freudencyclopedia.com.

- Additional historical analyses of Freud’s impact on medicine and societythepowercouple.caia601808.us.archive.orgindependent.co.uk.